A Multi-UAV Router and Scheduler for Executing Spatially Scattered Real-Time Tasks

Abstract

Cyber-Physical Systems (CPSs) operating in remote or field scenarios often face limited local processing capacity, necessitating complex real-time monitoring and control via remote processing through mobile edge networks, satellite systems, or UAVs. With recent advancements, UAVs are increasingly being favored for such applications, particularly in isolated areas beyond edge or satellite network coverage. This paper presents a unified UAV scheduling and routing framework for executing geographically distributed real-time CPS tasks under both periodic and aperiodic arrival models. We address the challenge of minimizing the number of UAVs required while ensuring strict adherence to task deadlines across diverse temporal and spatial settings. At first, we propose an efficient heuristic strategy called UAV Scheduling and Routing Algorithm for Real-time Tasks - Periodic Arrivals (), which decomposes applications into task instances and sequentially creates per-UAV routes and schedules within a hyperperiod, maximizing the number of task instances each UAV can cover while meeting deadlines. Adapting to this framework, we develop two additional variants to handle aperiodic CPS tasks: for Synchronous Aperiodic Arrivals (common arrival time, distinct deadlines) and for Asynchronous Aperiodic Arrivals (distinct but known arrival times and deadlines). For the case of periodic tasks, we frame the problem as a constraint optimization formulation which aims to minimize the number of UAVs that are required to generate static hyperperiodic travel routes with task execution schedules for all UAVs, and discuss how the formulation can be adapted for aperiodic tasks. Solution to this formulation using standard off-the-shelf solvers achieves optimality but incurs high computational overheads. Through extensive simulations, we show that exhibits high performance across diverse operational scenarios, varying task distributions, execution demands, and spatial layouts. The results emphasize ’s flexibility and effectiveness in real-world UAV-based CPS scenarios, especially in environments with limited resources and infrastructure.

Keywords and phrases:

UAV Scheduling, Task Allocation, Optimization, Execution TimeCopyright and License:

2012 ACM Subject Classification:

Computer systems organization Real-time system specification ; Computer systems organization Real-time system architecture ; Computer systems organization RoboticsEditors:

Renato MancusoSeries and Publisher:

Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik

Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik

1 Introduction

1.1 Proliferation of Real-time IoT Applications

Recent advancements in computing and communication technologies have led to a surge in Internet of Things (IoT) applications across various domains such as smart cities, industrial automation, healthcare, smart agriculture etc,. These IoT applications often require continuous control, sensing, and actuation, with strict demands on timeliness and reliability. For example, IoT-enabled smart agricultural systems monitor soil conditions and crop health in real-time, allowing for automated irrigation and fertilization based on live data feeds [30]. Similarly, predictive maintenance in industrial IoT (IIoT) leverages real-time data to monitor equipment performance, preventing unexpected breakdowns and optimizing operational efficiency [17]. In traffic management, IoT systems can monitor vehicle flow and congestion, detect road hazards, air quality etc. to perform real-time adjustments in traffic signals for improving road safety and reduce delays [1]. As the number and complexity of these IoT applications continue to grow, there is an increasing need for flexible/scalable computation and communication solutions in order to support the high bandwidth, low-latency processing and connectivity demands.

1.2 UAV-Based Execution of Real-time IoT Applications

Traditionally, computation, sensing and communication needs of IoT applications have been met using local on-board facilities. However in recent times, the limited processing facilities available on-board often become overwhelmed as the applications become progressively smarter, distributed, heterogeneous and complex in nature. To address this challenge, IoT systems have sometimes resorted to remote computation on nearby edge servers. Equipped with high bandwidth communication, such edge-based systems can become an attractive alternative mechanism for executing real-time IoT applications in diverse domains like agriculture, transportation, emergency response etc. However in many scenarios, such as remote or rapidly changing environments, fixed edge infrastructure may not be readily available.

To alleviate this problem, mobile edge computing implemented with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), are being envisaged as vital enablers for executing real-time IoT applications, particularly in environments where fixed infrastructure is either unavailable or impractical. Equipped with onboard processing capabilities and sensors, such as cameras, radar, and RFID readers, UAVs can independently handle real-time data acquisition and edge computation. Amodu et al. (2023) emphasize the crucial role of UAVs integrated with mobile edge computing to enable efficient data acquisition, processing, and communication in real-time scenarios [2]. This unique capability allows UAVs to perform end-to-end data collection, processing, and communication, making them indispensable for a wide range of mission-critical applications, particularly in environments where real-time performance is essential. For instance, in precision agriculture, UAVs equipped with multispectral sensors and onboard data processing capabilities monitor vast farmland areas, providing insights on crop health to optimize resource use and increase yields [4]. In search and rescue operations, UAVs equipped with thermal imaging sensors can rapidly scan large regions, providing real-time data on survivor locations [20]. Likewise, in urban environments, UAVs can analyze real-time video feeds to detect traffic congestion, accidents, or hazards, enabling quick interventions to improve traffic flow and safety [16]. By handling both sensing and computation onboard, UAVs eliminate the need for fixed edge servers, functioning as adaptable, autonomous platforms capable of meeting the dynamic demands of modern IoT applications.

1.3 A Survey on UAV-based Routing, Placement and Task Execution Strategies

The fundamental challenges in efficiently scheduling and routing UAVs for real-time task execution are closely related to classical combinatorial optimization problems, notably the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP), and Dial-a-Ride Problem (DARP). To efficiently manage the spatial distribution and time-sensitive execution of UAV tasks, these optimization problems offer valuable modeling insights. One such optimization problem, the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), seeks the shortest possible route visiting a set of locations exactly once and returning to the starting point, providing a foundational structure for single-UAV route planning [3]. On the other hand, the Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) extends TSP by considering multiple vehicles originating from a depot, each serving a subset of locations, thus naturally aligning with multi-UAV deployment scenarios [24]. Further, the Dial-a-Ride Problem (DARP) is a dynamic version of that generalizes VRP by introducing time-window constraints and pairing pickup and delivery points, making it particularly relevant for UAV-based real-time task execution where both timing and capacity constraints are critical [9].

In literature, the VRP and its variations have been widely studied, resulting in rich modeling frameworks and solution strategies that are highly relevant to UAV-based systems. For example, the Capacitated VRP (CVRP) imposes load capacity constraints on vehicles, while the Capacitated Electric Vehicle Routing Problem (CEVRP) incorporates limited driving ranges and non-linear charging behaviors, modeling the operational challenges faced by electric vehicles (EVs) [14, 15]. These VRP variants have seen extensive application in domains such as logistics, supply chain management, public transportation, and more recently, green transportation networks. Major industries including DHL, FedEx, XPO, and JD Logistics deploy VRP-based solutions for optimizing fleet operations under resource and energy constraints. Similarly, DARP has been instrumental in designing and optimizing on-demand ride services, paratransit operations, and dynamic shuttle systems, where tasks (pickups/deliveries) arrive dynamically, and operational schedules must adapt in real time. Importantly, these VRP/DARP modeling concepts extend beyond logistics or transportation and are equally applicable to mobile robotic systems like Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), Terrestrial Mobile Robots (TMRs) and Underwater Unmanned Vehicles (UUVs).

Drawing inspiration from these classical optimization problems, this work majorly concentrates on the real-time execution of a given set of spatially dispersed, static, periodic/ aperiodic control tasks using a minimum number of UAVs, by jointly optimizing per-UAV routing, task hovering durations and deadline-constrained task execution. Despite the numerous advantages, UAV-based IoT systems encounter significant challenges in reliably executing tasks within strict real-time deadlines. Efficient deployment and routing strategies are crucial for UAVs to effectively cover large areas or manage numerous spatially distributed tasks. Typically, these strategies are divided into static and dynamic approaches. Many deployments position UAVs at fixed locations within statically defined layouts, such as at the intersection points of logical grids. However, these static methods often lack flexibility to adapt to changes in user demand, task urgency, or environmental conditions [12]. In contrast, dynamic strategies allow UAVs to adjust their positions and routes in real-time to improve coverage, reduce latency, and enhance network reliability [32, 31, 29, 28].

Zhou et al. (2018) proposed an online multi-UAV repositioning methodology to dynamically adjust coverage based on emerging temporary events [32]. Building on this, Zhang and Duan (2019) introduced a fast UAV placement method to enhance wireless coverage and connectivity in areas with limited infrastructure [31]. The work by Zeng et al. (2016) optimized UAV paths to maximize data throughput in mobile relay systems [29]. To further improve communication efficiency, Zeng et al. (2018) designed UAV multicast schemes to minimize transmission time when delivering data to multiple ground users [28].

Recently researchers have also delved towards optimizing combined routing and hovering strategies for UAVs with the objective of enhancing distributed sensing and computation [2, 26, 8, 27]. Yu et al. (2020) developed an approach for using UAVs as mobile edge computing nodes and focused on joint task offloading and resource allocation to optimize energy efficiency and computational load balancing [27]. Yang et al. (2020) and Chen et al. (2024) designed real-time routing algorithms, which also take into account necessary hovering time for the execution of aperiodic real-time tasks using UAVs [26, 8]. The objectives of these works are to maximize the number of tasks that can be completed before their deadlines, and/or minimize energy consumption.

1.4 This Work: USRART-P, USRART-AS, USRART-AA

In this work, we consider both periodic as well as aperiodic, real-time tasks that are spatially distributed at fixed locations across a remote isolated region. Applications such as precision agriculture, search and rescue operations, traffic management, etc. are suitable candidates for these types of tasks. Applications such as say, continuous crop health monitoring and controlled fertilizer/ water delivery (in precision agriculture), are usually persistently repeating with specific sampling periodicities. Moreover, the application set may consist of multiple instances of the same type of application; for precision agriculture say, different application instances may be employed to serve distinct agricultural fields at different locations. In any case, the applications being static and periodic, the overall system has a hyperperiodically repeating cyclic nature. Within a hyperperiod, an application executes for a certain number of task instances. For such a scenario, this work considers the employment of a set of UAVs as real-time processing/ sensing resources, and proposes an efficient heuristic called UAV Scheduling and Routing Algorithm for Real-time Tasks - Periodic Arrivals (USRART-P).

Further, adapting this framework for aperiodic task scenarios, we develop two additional heuristic strategies: for Synchronous Aperiodic Arrivals (common arrival time, distinct deadlines) and for Asynchronous Aperiodic Arrivals (distinct arrival times and deadlines). is applicable to scenarios where multiple aperiodic tasks are triggered simultaneously by a single critical event. A representative example of such a scenario can be industrial facility accident management. For instance, in the event of a fire outbreak at a chemical plant at , multiple UAV tasks such as toxic gas sensing, pipeline integrity checks, and perimeter thermal scans, may be simultaneously launched to assess the situation. These tasks may have distinct urgency driven deadlines. For example, toxic gas sensing can be considered the most urgent and may have a shorter deadline compared to pipeline integrity check and thermal scan. is designed to manage such synchronously triggered yet deadline-diverse tasks, ensuring timely and prioritized execution.

Certain aperiodic tasks may have known arrival times within a specified time horizon, enabling higher scheduling flexibility compared to systems with synchronous task arrivals. In such scenarios, can be usefully applied. An example scenario arises with UAV-based last-mile delivery in smart logistics. In this context, package pickup and drop-off requests are specified with known release times and associated delivery deadlines within the operational horizon. For instance, it may be pre-scheduled that an urgent medical supply delivery task becomes available at time , while a food delivery request is set to arrive at . Further, medical supply delivery being more urgent may have a shorter relative deadline compared to food delivery. For such an use-case, can proactively schedule UAV routes, ensuring that each request is served within its deadline while maintaining efficient utilization of the UAV fleet.

All three variations of assume that each member of the set of UAVs starts from the same depot location at the beginning of a time horizon and flies over a subset of the task locations following a designated route, returning back to the depot by the end of that time horizon. During the traversal in its route, a UAV follows an alternating sequence of movement and hovering operations. The movement operation takes a UAV from one task location to another. At each task location, the UAV hovers for a specific time duration during which, it performs sensing and processing for the task. With the aim of minimizing the number of UAVs required, this work proposes an efficient methodology for generating per-UAV routes and deadline-meeting execution schedules for all tasks, aiming to maximize the subset of tasks that can be covered by each route. The major contributions of this work are thus summarized as follows:

-

This is possibly the first research work that presents a mechanism for UAV-based execution of a set of geographically distributed, periodic as well as aperiodic real-time applications. We have systematically analyzed the underlying problem structure and represented it in the form of a constraint optimization formulation.

-

We have proposed an efficient but low-overhead heuristic approach called “UAV Scheduling and Routing Algorithm for Real-time Tasks ()”, for the problem at hand. With the aim of minimizing the number of UAVs, generates routes with deadline-meeting task schedules for each UAV.

-

We propose three adaptations of namely, for periodic real-time tasks, for synchronously arriving aperiodic tasks and for asynchronous aperiodic tasks with known arrival times.

-

We have conducted extensive simulations to rigorously evaluate our algorithms using diverse datasets inspired by plausible real-world scenarios. Our experiments span a wide range of conditions, varying task densities, spatial distributions, task execution times, and UAV speeds. The experimental results show that all variations of USRART consistently deliver appreciable performance across diverse test cases, highlighting their robustness, generic nature, and practical applicability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the system model and problem formulation. Section 3 provides a detailed description of the proposed algorithm. Finally, Section 4 discusses the experimental setup and results, demonstrating the effectiveness of our proposed approach.

2 System Model

In this section, we formulate the system models for both periodic and aperiodic real-time CPS tasks targeted for UAV-based execution. We first present the model for periodic tasks, laying the foundation for subsequent extensions to handle aperiodic task arrivals. For the first case we consider a set of periodic real-time applications, denoted by , where each application is characterized by a four-tuple . Here, denotes the geographical location of application , and denotes the execution requirement and period of respectively. Data communication overhead between a UAV and ’s ground location , is assumed to be incorporated within the execution time of . We denote by the hyperperiod of the set of applications; thus, . Given that all applications are ready to execute at the system start time “”, represents the smallest interval after which the arrival of all applications simultaneously synchronize again. The number of jobs of any application within is given by , with the jobs being . The total number of jobs to be executed within is given by ; .

A fleet consisting of homogeneous Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs)

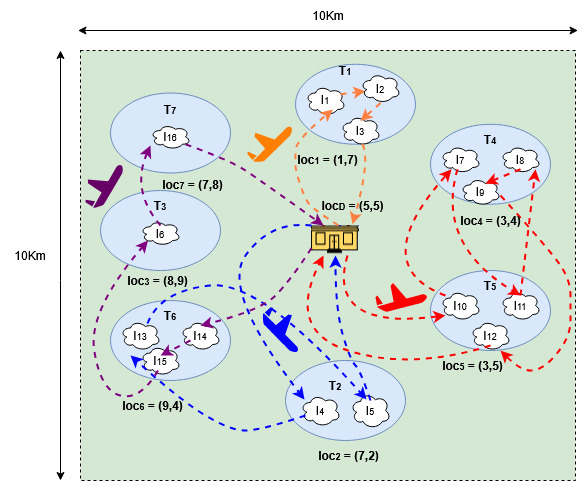

having same computational capacity and identical flight speed , is deployed to execute the list of jobs. At the beginning of each hyper-period, all UAVs start from a common depot location (Refer Figure 1). Then they follow distinct UAV-specific routes moving and hovering over a subset of job locations, and finally return back to the depot by the end of the hyper-period (as depicted in Figure 1). The depot location thus act as both the origins and ultimate destinations of all UAV routes.

The UAVs are oriented towards the execution of individual jobs; that is, two distinct jobs say, and of the same application , may be executed by different UAVs. Thus, we represent all jobs of all applications within the duration , as a single sequential list of task instances . The sequence begins with jobs from application , followed by , and continues sequentially through . The task instances, correspond to the jobs , instances represent jobs , and so forth, with denoting . Moreover, as all UAVs start and finish their journeys at the depot, we add origin and ultimate destination dummy task instances and respectively, corresponding to the UAV routes.

Each UAV covers a disjoint subset of task instances in its route. A UAV route , represents an ordered list of task instances assigned to UAV (), where indicates that the location in ’s route is dedicated to task instance . Here, and . Route set } refers to the collection of UAV routes. Each task instance is described by a 10-tuple: which defines its execution and scheduling related parameters. We now describe the significance of each of these ten parameters of a task instance :

-

(i)

Application id (): Identifier of the application of which is a task instance.

-

(ii)

Job id (): Identifier of the job which corresponds to the instance .

-

(iii)

Release Time (): Represents the earliest time at which instance becomes available for execution. Since is the job of the periodically repeating application , its release time is computed as:

(1) -

(iv)

Deadline (): Latest time by which execution of must complete. It is given by:

(2) -

(v)

Execution Time (): The execution time of all instances of a task is same. Hence, .

-

(vi)

Location (): The location of is derived from the location of task . That is, .

-

(vii)

Travel Time (): Let, be the task instance in UAV ’s route ; that is, . Now, travel time is the time required to reach () from , the location of the task instance covered by the element of route .

(3) In the above equation, is a function which returns the euclidean distance between the task instances covered by and and is the speed of UAV .

-

(viii)

Start Time (): The start time of represents the instant when its execution begins on . Now, start time is given by:

(4) Here, denotes completion time of the instance covered by . Therefore, is obtained as the higher between the time instant at which is released and the time instant at which reaches .

-

(ix)

Completion Time (): This is represented as:

(5) -

(x)

Slack Time (): Slack denotes the maximum duration by which start of can be delayed while ensuring deadline adherence. It is defined as:

(6)

Finally, for any origin dummy task instance (corresponding to UAV ), = = = = = = , and . Similarly, for any destination instance , and .

2.1 An Example Application and System Scenario

We consider here, a real-time military surveillance system described as follows. The system requires to surveil seven geographically scattered sites () within a given region of size 10 km × 10 km, as shown in Fig. 1. Each site is surveilled by a UAV which periodically comes and performs surveillance. This surveillance job is conducted by scanning and collecting information (such as potential enemy movements and/or rescue needs) from the area of the site, with the help of camera-equipped UAVs or via cameras installed at terrestrial locations. In addition, the UAVs may also be equipped with processing power in order to say, perform periodic adjustments of the pan-tilt-zoom settings of the installed cameras, based on received image/video feeds. The activities in a job thus include scanning, data transmission (information collection) and computation. The potential sequence of jobs associated with a particular site say , constitutes a distinct periodic real-time application . The execution time (of ) depends on the total time required by a UAV to perform all the mentioned activities associated with a job say, . This execution time depends on factors such as, area of the site to be scanned, number of installed cameras, size of transmitted data and computation time required to generate control outputs say, new pan-tilt-zoom setpoints. Periodicity of surveillance may depend among other factors on the sensitivity of the site w.r.t surveillance. Thus, high-risk sites which are say, prone to enemy activity, may require to be more frequently surveilled at shorter intervals, compared to others.

Table 1 depicts the execution times, periods, and site locations of all the seven periodic applications considered in the problem. The hyper-period of these applications is . The number of jobs of each application within one hyper-period has also been shown in Table 1. The objective of the problem is to deploy the minimum among a set of available UAVs which are homogeneous in terms of their flight speed (here, 30 km/h), processing capability, as well as data collection/transmission rate. All deployed UAVs should start from their designated depot location () at the beginning of each hyper-period, cover a subset of jobs, and return back to the depot by the end of the hyper-period. Fig.1 shows a solution to this problem scenario using the proposed algorithm (described later). It may observed that requires the deployment of four UAVs to solve this periodic real-time routing cum scheduling problem. The above running example is motivated by the real-world military surveillance operation

The above example is motivated from the requirements of modern day military surveillance (as detailed in [18]) which underscore the critical need for efficient UAV routing and task allocation in remote, high-risk environments.

| Application | Location | Period (mins) | Exec. Time (mins) | No. of Jobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| = (1, 7) | = 10 | = 1.0 | = 3 | |

| = (7, 2) | = 15 | = 0.5 | = 2 | |

| = (8, 9) | = 30 | = 2.0 | = 1 | |

| = (3, 4) | = 10 | = 1.5 | = 3 | |

| = (3, 5) | = 10 | = 1.0 | = 3 | |

| = (9, 4) | = 30 | = 1.3 | = 1 | |

| = (7, 8) | = 10 | = 1.9 | = 3 |

System Model Adaptations for Handling Aperiodic Real-Time Applications

Unlike periodic tasks, aperiodic applications are modeled as single-instance tasks. The system model considers aperiodic tasks , each arriving at arbitrary times rather than following a periodic pattern. The attributes associated with an aperiodic task has however been kept exactly same as that of a single periodic task instance, discussed above; an aperiodic task is described as : . The only difference is that, unlike the periodic model where each job instance carried a distinct job identifier () corresponding to its instance in the periodic sequence, the aperiodic model omits this job ID, as each application represents a unique, single-occurrence task. The aperiodic model supports two subclasses of aperiodic arrivals in this work: and as described in the Introduction section. All other assumptions and structural elements of the system model – such as UAV capabilities, depot behavior, and routing formulation – remain consistent with those described for the periodic case.

An Example Application for Aperiodic Scenario

We now consider an aperiodic system where UAVs perform last-mile deliveries within a smart logistics network spanning a 10 10 km zone, identical to the setup in the periodic scenario. Each site represents a one-time aperiodic delivery request with its own release time, execution time, and deadline. For instance, if all delivery requests are known at the start () but have varying deadlines – such as multiple urgent packages to be dispatched in one planning window – this maps to the USRART-SA scenario. Alternatively, if requests arrive over time, such as a medical supply delivery becoming available at and a food delivery request at , this aligns with the USRART-AA case. UAVs handle package pickup, transport, and drop-off, starting and ending at the central depot (5, 5), similar to the periodic model. This type of UAV scheduling ensures that each delivery request meets its individual timing constraints while ensuring efficient utilization of the fleet.

3 The Problem Formulation

We now describe the problem formulation that determines per-UAV routes for efficiently executing a given set of geographically distributed real-time applications, using a minimum number of UAVs. It uses a set of binary decision variables of the form (, and ).

Among them, the subset of decision variables having type involves the origin task instance for a UAV . Similarly, the decision variables are those which involve the dummy task instance at the final destination of a UAV . Any variable , denotes that the UAV directly moves to task instance from ; , otherwise. Next, we discuss the objective function and constraints.

Objective Function.

Given an upper bound on the number of available UAVs, the objective is to determine the minimum number of UAVs, which are necessary to execute a geographically distributed set of real-time tasks. Let form the set of active UAVs while form the set of inactive UAVs that are not actually deployed. Additionally let, , for the UAV. Now, it may be observed that if the UAV has non-zero route length (active), then and, . Hence, the objective function becomes:

| (7) |

Constraints.

There are four constraints in this formulation.

-

1.

Unique UAV, unique source constraint: For any instance , there is a unique UAV which arrives to it after immediately serving a unique previous instance .

(8) -

2.

Unique UAV, unique destination constraint: For any instance there is a unique UAV which serves it and then moves to a unique destination instance .

(9) -

3.

Non-zero route length constraint: To ensure the generation of non-zero-length routes for all active UAVs, we enforce the following,

(10) -

4.

Deadline constraint: Each task instance should complete execution before its respective deadline. To mathematically represent this constraint, we use the route elements (, ; discussed above) as auxiliary variables. It may be observed that all values can be derived for a fixed valuation of the decision variables . Additionally, we set: , . Thus, the route element of a UAV corresponds to its origin task instance . Similarly, we set: , , indicating that the last route element of is . Given the values of , the deadline constraint can be written as:

(11)

Equations 2 and 5 above discuss the mechanisms for determining values of and . It may be observed that by enforcing constraint 11 for , for any UAV , we restrict the total route time for to be upper bounded by .

The above problem formulation involves a large number of variables and constraints making it computationally very expensive. Hence, we have not used standard optimizers (like CPLEX [13]) to solve the problem. We highlight that the main motivation to formally represent the problem as above is to clearly show the nature/structure of the scheduling problem being solved.

4 Proposed Algorithm: USRART

The UAV Scheduling and Routing Algorithm for Real-time Tasks (; Algorithm 1) is a heuristic algorithm aimed at efficiently allocating a minimum number of UAVs for executing all task instances of a given set of independent periodic/ aperiodic applications. We present three tailored variants of the framework, namely , , and , each designed to address specific scheduling scenarios as detailed below.

first generates a single list of all task instances (of all these applications) that are spawned within one hyper-period duration. For all task instances, attributes such as release time, location, execution time, and deadline are noted. Initially, these task instances are unmapped, that is, not allocated to any UAV for their execution. Next, iteratively calls a function called UAV Route Generator (; Algorithm 2) until all task instances have been mapped to its designated UAV.

The function constructs the route for a single UAV. This route starts from the depot at the beginning of the hyper-period and ultimately returns back to the depot at the end of the hyper-period. As discussed earlier, a route is a sequence of task instances which are allocated for execution to this UAV. The time consumed by a generated route () consists of the UAV’s total travel time, as well as its aggregate waiting times and execution times for all task instances in the route. Obviously, the value of this route time is upper bounded by , the hyper-period duration. The route is constructed by iteratively adding additional task instances in a sequential manner, until no more task instances can be added while not violating the route time constraint. At any instant after allocating a task at a certain location during partial route generation, attempts to find the best unmapped task instance (having highest Goodness; refer equation 12) that should be appended to the current partial route. We now provide a more detailed step-by-step explanation of both the algorithms, namely and .

4.1 Function : Detailed Description

takes as input a set of n applications. The output of the algorithm is a route set (), which contains the routes for all deployed UAVs. The algorithm begins with four initialization steps. Line 1 initializes the global list of task instances () from the input application set () and computes essential attributes for each task instance including, release time (), deadline (), execution time (), and location () (Refers Section II, System Model). In Line 3 we initialize a boolean array map[] of size . An element , indicates that task instance has already been mapped to a UAV route; , if is still unmapped. Line 4 initializes a global array thread[], which threads together the first instances of each application within list . Lines 5-8 initiate an iterative process where UAVs are deployed sequentially until all task instances are assigned. In each iteration, the (UAV Route Generator) function is called to compute an efficient route based on task constraints, for a new UAV . The route is then added to the UAV route set , and the process repeats until all tasks in are mapped. Example Continued: Following table 1, we generate a set of task instances , derived from the given set of seven applications. For each , the algorithm computes , , and . As example, for ; instance of ) we have, = 30, = 45, = 0.5 and = (7,2). The array thread[] which holds position indices (within list ) of the first instances of each application, gets initialized as thread[] = .

4.2 Function : Detailed Description

The (UAV Route Generator) function is designed to generate an efficient route for each UAV (). The algorithm takes two inputs: the UAV identifier and an array map[] that tracks task instances that have not yet been assigned to any UAV. The output is a route which specifies the sequence of task instances assigned to .

The while loop in Lines 5 to 28 sequentially adds new task instances to UAV ’s route as long as the total route time remains less than the hyper-period . At any time during partial route generation, the for loop in Lines 7 to 22 attempts to append the best task instance (whose index in is stored in ) among all unmapped instances over all applications, to the current partial route = . For any given application , the while loop in Lines 8 to 22 first attempts to find the earliest instance of that can be feasibly accommodated into ’s route. For an unmapped candidate task instance say to be eligible for inclusion into at position , the following conditions must be satisfied. First, the UAV which is at location at time must be able to travel to ’s position, then either start immediately or wait (Refer eq. 4) until the release of at time (Refer eq. 1), and finally be able to complete execution before (Refer eq. 2), the deadline of . The deadline check is performed as part of the condition in Line 13. The condition in Line 17 is necessary to ensure that the length of route remains within the hyper-period duration after the inclusion of . If a candidate instance is deemed to be feasible, its Goodness is computed in Line 21. The value of Goodness which is used to determine the most eligible candidate task instance that should be added to at , is computed as:

| (12) |

In the above equation, denotes the tentative relative slack that will remain after completion of execution, if is actually selected for inclusion at . The value of is computed as: , where is the actual tentative slack (Refer eq. 6) associated with ’s inclusion, and denotes the maximum possible slack that may possibly be enjoyed by any task in the system. A lower value of indicates a relatively higher urgency w.r.t inclusion of in ; thus in equation 12, .

The value of is computed as: , where represents the total travel time and waiting time that must be spent by UAV , after completion of the last task instance () in its current partial route, and before the start () of ’s execution. On the other hand, represents the maximum travel and waiting time that can possibly be spent by a UAV between the completion of execution of a task instance and start of execution of the next instance, in any feasible route which does not violate deadlines. It may be noted that for a candidate instance , if is relatively higher, it indicates that the UAV wastes relatively more time travelling and waiting than more useful task execution, ultimately resulting in lower resource utilization. Thus, .

The parameter quantitatively represents the relative density of tasks within a stipulated radius111: The value of is an input constant to the problem and remains same for all tasks around ’s location. Density is formulated as: where, denotes the number of tasks within radius , around , while () is the maximum (minimum) number of tasks found within radius , across all task locations within the region being considered in the problem. For a candidate instance a relatively higher value of indicates a lower density of tasks around . It may be noted that, if a candidate located in a sparsely dense area is selected for inclusion in ’s route, the likelyhood of higher travel and waiting times in the future route of , will increase. Thus, .

In equation 12, has been designed to be inversely proportional to the linear combination of , and . Here, are positive quantities; . If is better than the best Goodness seen so far (; Line 21), and are updated (Line 23). After all instances have been considered, the instance is added to (Line 27), current time and route length are updated (Lines 28 and 29) and is marked as mapped (Line 30). Finally we consider the case where no new task instances can be feasibly added to the current route . In this case, remains null after evaluating all task instances. We set the route length and add the destination dummy instance to route , in Line 25 and update total route time () in Line 26.

Example Continued: Continuing further with our running example (Refer “An Example System”, Section 2, and “Example Continued”, Section 4.1), Table 2 presents the final UAV routes and execution schedules generated by for the scenario described earlier. It may be observed that the solution requires four UAVs }. Out of the 16 task instances in , covers six instances, and covers three instances each, while covers four instances. The table also depicts the relative slack , relative total time , relative density , Goodness , start time and completion time for each instance . Gantt charts of the final routes and schedules have also been depicted in Fig. 2. We see that as is necessary, total route times for all UAVs is less that . A diagramatic representation of the final routes has been shown in Fig. 1.

| UAV | Instance | Rel. Slack | Rel. Total | Relative | Goodness | Start | Completion |

| () | () | Time () | Time () | Density () | () | Time () | Time () |

| () | 0.1742 | 0.0849 | 0.0 | 0.0947 | 4.0 | 5.0 | |

| () | 0.0522 | 0.0424 | 0.5 | 0.1369 | 7.0 | 8.5 | |

| () | 0.2961 | 0.0424 | 0.0 | 0.1100 | 10.5 | 11.5 | |

| () | 0.1742 | 0.0424 | 0.5 | 0.1735 | 13.5 | 15.0 | |

| () | 0.2961 | 0.1061 | 1.5 | 0.4419 | 15.0 | 21.5 | |

| () | 0.1916 | 0.0424 | 2.0 | 0.4787 | 23.5 | 24.5 | |

| () | 0.2539 | 0.1531 | 0.5 | 0.2527 | 7.21 | 7.71 | |

| () | 0.5342 | 0.1201 | 1.0 | 0.4203 | 13.37 | 14.67 | |

| () | 0.3196 | 0.1201 | 1.5 | 0.4559 | 20.32 | 20.82 | |

| () | 0.0019 | 0.1899 | 1.0 | 0.2955 | 8.94 | 9.94 | |

| () | 0.3135 | 0.0011 | 2.0 | 0.4946 | 9.94 | 11.0 | |

| () | 0.3135 | 0.1911 | 2.0 | 0.5896 | 11.0 | 21.0 | |

| () | 0.0309 | 0.1531 | 1.5 | 0.3858 | 7.21 | 9.11 | |

| () | 0.2822 | 0.0188 | 1.5 | 0.3941 | 9.11 | 11.9 | |

| () | 0.4624 | 0.0600 | 1.5 | 0.4687 | 14.72 | 16.72 | |

| () | 0.2822 | 0.0694 | 2.0 | 0.5194 | 19.56 | 21.9 |

4.3 and

The aperiodic variant retains the overall structure of but introduce key changes to handle possibly distinct but known arrivals as well as deadlines. Feasibility is now checked by ensuring that each task starts no earlier than its arrival time and completes before its deadline. The pseudocode for this scenario is presented in Algorithm 3. A new array, skip, tracks tasks that UAV cannot feasibly serve, enabling early pruning and improving efficiency. The while-loop is updated: unlike the periodic case where tasks were added while route time stayed below hyper-period , here it continues until all tasks are scheduled or skipped. Also, unlike which used a thread[] array to manage multiple task instances, aperiodic tasks are treated as single applications without instances. Further, in cost calculations, the parameter period in relative slack and relative total time terms (, ) is replaced by the task’s deadline to align with aperiodic constraints. The rest, including density formulations and overall cost structure, remains as in . is identical to except the fact that assumes a common arrival time unlike which handles individual known arrivals.

5 : Time Complexity Analysis

For the periodic task scenarios the core computational effort in lies in the repeated calls to the function. Each invocation of generates a route for a single UAV. During this process, the algorithm iterates over applications, evaluating approximately task instances per application. Since computing the goodness metric for each task instance requires time, the total complexity per invocation of is . Given that is called up to times within , the overall worst-case time complexity of USRART is: . As, , where , we can express the overall complexity as . For the aperiodic task scenarios, the overall time complexity remains the same, i.e., , since the algorithmic structure of remains unchanged.

6 Experimental Evaluation

The performance of the proposed algorithms namely , and has been evaluated using extensive simulation based experiments. However our approach could not be benchmarked against any existing algorithm because we could not find any notable existing framework having a comparable problem model as considered in this paper. This is possibly because UAV-based remote execution of real-time CPS tasks is a very futuristic and emerging research topic. Additionally as discussed in section 3 (The Problem Formulation), design of routing and scheduling strategies for this setup is significantly complex. In the absence of a comparable state-of-the-art work, we have compared against two baseline heuristics and as described next:

-

: In this case, instead of using the Goodness metric (equation 12) used in , here we employ a simpler Goodness function which disregards relative density :

(13)

Next, we discuss the data generation framework for all variations of in detail. For the aperiodic case, we adopt only as the baseline, as , which relies on random selection, has been observed to perform poorly across all cases in the periodic scenario. Thus, is not considered for the aperiodic case.

6.1 Data Generation Framework

An exhaustive set of experiments has been performed using carefully designed synthetic datasets to evaluate the performance of in various plausable real-world scenarios that it may encounter in practice. To derive essential real-time task parameters such as periodicities and execution times, we have conducted relevant surveys on real-world UAV application scenarios. For example in precision agriculture, UAVs are utilized for crop health monitoring, pest detection, and irrigation management, which require detailed flight paths over agricultural fields, data capture via sensors, and real-time data analysis. Each task typically takes between 5 to 15 minutes, considering the time required for UAVs to navigate the area, capture necessary data, and transmit it for processing [25]. Similarly, traffic management applications, where UAVs monitor traffic flow, congestion, or accidents, demand high-resolution imaging and density estimation. These tasks usually require 20 to 25 minutes per zone, depending on the area size and urban density [11]. Other significant UAV applications include search and rescue missions, where UAVs navigate disaster zones to locate victims or deliver supplies. These operations typically require around 30 minutes, as the UAVs must cover large areas while coordinating with on-ground teams [10]. In military contexts, UAVs are used for surveillance and reconnaissance, with missions ranging from 15 to 45 minutes, influenced by the complexity of the task and the geographical challenges involved [18]. Additionally, UAVs are increasingly used for environmental monitoring, for tasks like air quality assessment, water resource management, and deforestation analysis, with tasks typically taking 14 to 20 minutes for comprehensive data collection and processing [6]. Based on the above studies we have attempted to construct a data generation framework which should be able to ensure that experimental analysis is applicable to real-world scenarios while being also adaptable for future benchmarking efforts. The common parameters used in the experiments discussed in Section 6.2 below, are described as follows:

-

Application locations: Locations are randomly generated using a uniform distribution within a fixed grid size of for all experiments apart from experiment 3. In experiment 3, we have generated the locations using a normal distribution as discussed later in Section 6.2.

-

Application Count: In experiments 2 and 4, we run the heuristics for 50 applications whereas for experiments 1, 3, 5 and 6 we run them for both 50 and 100 applications.

-

Application Periods: The period of each application, in the context of the periodic case experiments, is randomly selected uniformly from the range [10 mins, 50 mins], aligned with the application scenarios discussed above.

-

Application Deadlines: For experiments 5 and 6, application deadlines are randomly selected within 20 to 180 minutes.

-

Application Arrival Times: For experiments 5 and 6 (aperiodic tasks), arrival times are randomly selected within [0, 135] minutes. The range starts from 0 to align with the case (where all applications arrive at ), while 135 minutes serves as the upper bound for varied arrival patterns.

-

Application execution times: For experiments 1 to 4 (periodic tasks), application execution times are generated from the range [0.5 mins, 2.5 mins] using a normal distribution with mean mins and standard deviation mins. To evaluate the impact of task execution time variation, execution times are progressively increased along the x-axis in steps of 10 for experiments 1, 2, and 4. For aperiodic task experiments (5 and 6), execution times also follow a normal distribution with mins and mins, bounded between 0.5 and 19.5 minutes, with the same 10 incremental variation applied across both USRART-SA and USRART-AA.

-

UAV speed: In Experiments 1,4 and 5 the UAV speed is fixed at 30 km/h (0.5 km/min) to maintain consistency in travel time calculations across different task counts. In Experiments 2,3 and 6, UAV speeds of 0.5 km/min, and 1 km/min are used to analyze the effect of the variation in speed on Average UAV Count.

Performance Metrics

The following two metrics have been used to evaluate the performance of :

-

UAV Count: The number of UAVs required to cover all task instances using a given heuristic algorithm, is calculated for each test case.

-

Algorithm runtime: The proposed heuristic approaches are evaluated based on the time required to compute the UAV routes and associated task schedules.

6.2 Results

To evaluate the performance of all variations of and compare them against baseline heuristic strategies, six experiments have been conducted. All experiments apart from experiment 4 measure the number of UAVs required to generate UAV routes and task schedules, against increase in task execution times, variations in task location density, change in UAV speeds and variation in the number of applications. Experiment 4 on the other hand, depict runtimes of the algorithms as task execution times are varied on the x-axis. The value of each result point in the plots for any of the depicted experiments represents the average over 500 test cases derived from a designated fixed set of parameter values. In order to compute Goodness for , the parameters , , and are multiplied with empirically derived weight constants , , and , respectively. Similarly, for in the periodic setting, we use weight constants as and whereas in the aperiodic cases, we assign and .

6.3 Experimental Analysis for USRART-P

Experiment 1: UAV Count Vs. Exec. Time, for Different Applications

We analyze here, the impact of execution time variations on UAV deployment. In the experiment, we compare two scenarios. The first scenario consists of 50 tasks while the second scenario consists of 100 tasks distributed within the same area. For both the scenarios, UAV speed is kept fixed at 0.5 km/min. The results in Figure 3 highlight that as obvious, number of UAVs required rises linearly with both the number of applications as well as increase in task execution times. The trends thus confirm that required UAV count increases as resource demands grow, with larger task sets exhibiting sharper increase in UAV counts. From the comparative analysis, we observe that the proposed algorithm performs more efficiently as compared to the other two baseline heuristics. , which randomly selects tasks without considering Goodness, results in a significantly higher UAV count compared to both and . On the other hand, which ignores task density when choosing the next task instance to be appended to be a route, shows poorer performance compared to , demonstrating the necessity of incorporating all three factors (slack time, total time, and density) in task selection.

Experiment 2: UAV Count Vs. Exec. Time, for Different UAV Speeds

This experiment evaluates the number of UAVs required to execute a set of 50 real-time periodic applications, as average execution times of these tasks is progressively increased on the x-axis. Here also we consider two scenarios, the first of which assumes speed of the UAVs to be 0.5 km/min while the second assumes the speed to be 1.0 km/min. The results in Figure 4 reveal that higher UAV speed leads to a reduction in the number of UAVs required as faster UAVs can cover more task instances within the same timeframe. However, for a fixed value of speed, a higher number of UAVs are required as average task execution times increase. Lastly similar to Experiment 1, performs consistently better than performs better than .

Experiment 3: UAV Count Vs. Sparsity of Application Locations, for Different UAV Speeds

Here, we analyze the impact of the variation in application location sparsity on the number of UAVs required to cover 50 applications within a rectangular 10 km 10 km region (left-bottom corner = (0, 0), right-bottom corner = (10, 10)). A Dataset corresponding to a certain sparsity is obtained by deriving the location values from a normal distribution having mean and standard deviation (, ) where denotes a particular x-axis label ( [0,5]). For example when = 2, all 50 application locations are drawn from the normal distribution having and ; thus, the location (4, 6) can be a sample element from this distribution which falls within one-standard-deviation. As may be observed from the x-axis in Figure 5, we have conducted experiments with datasets having progressively higher sparsity, from to . The special case captures the scenario where all applications are concentrated only at the centroid location (5, 5). We observe that the UAV count rises as standard deviation increases. Figure 5 shows that as the standard deviation increases, the UAV count rises. A higher standard deviation spreads tasks farther from the centroid – resulting in longer travel distances and necessitating more UAVs – while a lower standard deviation concentrates tasks, reducing UAV requirements. Similar to the other experiments, we see that consistently outperforms both (random selection) and (ignoring density), achieving the lowest UAV count across all task sparsity levels.

Experiment 4: Avg. Runtime vs. Exec. Time, for Different Applications

In this experiment, we examine how variations in task execution times and application counts impact runtimes of the three heuristic algorithms evaluated. All values are measured in milliseconds. We examine two scenarios: one where 50 tasks are distributed throughout the area, and another where 100 tasks are spread over the same region. In both cases, the UAV operates at a constant speed of 0.5 km/min. The results, illustrated in Figure 6, reveal several key observations. First, for a lower application count (50 applications), the average algorithm runtime remains relatively stable across different execution time variations. This suggests that for smaller workloads, fluctuations in application execution times do not significantly impact algorithm runtime. However, as the number of applications increases to 100, the algorithm runtime becomes noticeably higher and fluctuates more with change in the execution times of applications. A comparative analysis of the different methods highlights that due to its higher computation intensiveness incurs higher runtime overheads compared to both and . This is because it uses the Goodness metric for the purpose of task instance selection within a partial route, which incurs higher overhead. , which does not account for density, shows moderate algorithm runtimes while is the fastest.

6.4 Experimental Analysis for USRART-SA and USRART-AA

Experiment 5: UAV Count Vs. Exec. Time, for Different Applications

This experiment studies how increasing execution time affects UAV count, considering two scenarios (50 vs. 100 tasks) while keeping UAV speed fixed at 0.5 km/min. Figures 7a and 7b illustrate the results corresponding to and , respectively. The results show a linear increase in UAV count as execution time rises, with a sharper increase for the 100-task scenario due to higher resource demand. This trend remains consistent for both cases, demonstrating that execution time directly impacts UAV allocation, regardless of arrival time variations.

Experiment 6: UAV Count Vs. UAV Speed, for Different Applications

This experiment evaluates how UAV speed variations affect UAV count. Figures 8a and 8b illustrate the results corresponding to and , respectively. The results confirm that reducing UAV speed lead to a higher UAV count, highlighting its importance in UAV allocation. The trends remain consistent for both cases, indicating that the effect of speed is independent of task arrival characteristics.

Both and consistently outperform the baseline , achieving the lowest UAV count while maintaining efficiency. In contrast, , which neglects density considerations, performs noticeably worse and fails to optimize UAV distribution effectively. These results underscore the importance of jointly considering slack, total time, and density to achieve minimal UAV allocation.

7 Discussions

To further contextualize the presented framework, we discuss two critical aspects: its generalization to broader application domains, and practical operational constraints/limitations that influence real-world UAV deployments.

7.1 Applicability of USRART to Other Application Domains

The methodologies developed in this work are not limited to UAV based systems but can be applied to other autonomous mobile systems operating in similar constrained and dynamic environments. Two representative domains are discussed below:

Domain 1 – Terrestrial Mobile Robots (TMRs).

Terrestrial mobile robots are increasingly deployed for ground-based operations, especially in environments where human intervention is risky or inefficient [22]. A representative use-case is hazardous area surveillance in mapped industrial plants, post-disaster zones, or research facilities. Consider a scenario where mobile robots are dispatched from a central depot to inspect critical zones, gather environmental data (e.g., radiation, temperature), and return. These inspection tasks can be modeled either as periodic (routine surveillance at fixed intervals) or aperiodic (emergency inspections triggered by alarms). In both cases, the synchronous release models and real-time scheduling strategies proposed here can be effectively adapted to ensure timely task execution and safe robot operation.

Domain 2 – Underwater Unmanned Vehicles (UUVs).

UUVs perform complex missions in harsh underwater environments where intermittent communication and energy constraints are significant challenges. A typical application is the inspection of subsea pipelines [5], cables, or waste containers. Here, UUVs are deployed from a vessel or underwater dock to a set of inspection points. Periodic inspections (scheduled dives) and aperiodic inspections (triggered by detected anomalies) mirror the task release models discussed in this work. Careful scheduling and routing are essential to accommodate energy limitations and operational deadlines, making the proposed framework directly suited to this domain.

7.2 Consideration of Practical Operational Constraints

For obtaining accurate solutions through the proposed framework, a few practical operational constraints may be needed to be considered depending on the specific deployment scenario at hand. A few important operational constraints include:

-

Battery Constraints: UAVs have limited battery capacity, and their energy consumption varies based on flight dynamics, hovering time, and onboard computation. Accurate energy modeling is crucial to prevent mission failures due to unexpected depletion. Recent studies have proposed mathematical models to capture these energy dynamics in the context of routing problems [7].

-

Recharging Logistics: Incorporating recharge or battery-swap stations adds further complexity to the scheduling and routing problem. This aspect aligns with the Electric Vehicle Routing Problem (EVRP), where vehicles plan their paths considering limited energy reserves and intermediate recharging stops [19]. Leveraging such ideas will be essential for extended-duration UAV missions.

-

Environmental Factors: External environmental conditions, particularly wind and weather variability, significantly impact UAV flight stability, energy usage, and latency. Experimental studies have demonstrated how wind disturbances alter UAV performance [21]. Advanced nonlinear guidance and robust control techniques have also been proposed to ensure safe operation under strong wind conditions [23]. Integrating adaptive and robust planning mechanisms is critical for reliable UAV mission execution in varying environmental settings.

8 Conclusions and Future Work

This paper addresses the problem of UAV-based routing and scheduling for executing a set of geographically distributed, real-time Cyber-Physical System (CPS) applications. Since an optimal solution to this problem proves to be computationally expensive, we have proposed an efficient but fast heuristic strategy called UAV Scheduling and Routing Algorithm for Real-time Tasks (). systematically decomposes the problem by generating per-UAV routes and schedules, iteratively mapping tasks while maintaining deadline constraints. We propose three algorithm variants: (periodic tasks), (synchronous aperiodic), and (asynchronous aperiodic). generates per-UAV routes within a hyperperiod to maximize task coverage under deadline constraints. and iteratively allocate UAVs based on task availability and urgency, ensuring real-time guarantees. Through extensive simulations, we have demonstrated that maintains high performance across diverse operational scenarios, varying task distributions, execution demands, and spatial layouts. The results highlight ’s adaptability and practical utility in real-world UAV-based CPS application scenarios, particularly in resource-constrained and infrastructure-limited environments.

As future work, we plan to focus on enhancing by incorporating dynamic task arrivals, UAV energy constraints and collaborative multi-UAV strategies to further improve robustness and real-time adaptability in practical deployments. Furthermore, extending to handle stochastic execution times and travel uncertainties would make it more applicable to real-world conditions where unexpected delays are inevitable. Finally, real-world deployment and experimental validation in diverse terrain conditions would help refine the algorithm’s performance and reliability. Addressing these challenges will further enhance UAV-based CPS task execution, making it a scalable and resilient solution for autonomous operations in remote environments.

References

- [1] Mansoor Akhtar, Muhammad Raffeh, Fakhar ul Zaman, Ali Ramzan, Sohaib Aslam, and Faisal Usman. Development of congestion level based dynamic traffic management system using iot. In 2020 international conference on electrical, communication, and computer engineering (ICECCE), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2020.

- [2] Oluwatosin Ahmed Amodu, Rosdiadee Nordin, Chedia Jarray, Umar Ali Bukar, Raja Azlina Raja Mahmood, and Mohamed Othman. A survey on the design aspects and opportunities in age-aware UAV-aided data collection for sensor networks and internet of things applications. Drones, 7(4):260, 2023.

- [3] David L. Applegate, Robert E. Bixby, Václav Chvátal, and William J. Cook. The Traveling Salesman Problem: A Computational Study. Princeton University Press, 2007.

- [4] Muhammet Fatih Aslan, Akif Durdu, Kadir Sabanci, Ewa Ropelewska, and Seyfettin Sinan Gültekin. A comprehensive survey of the recent studies with UAV for precision agriculture in open fields and greenhouses. Applied Sciences, 12(3):1047, 2022.

- [5] Martin Aubard, Sergio Quijano, Olaya Álvarez-Tuñón, László Antal, Maria Costa, and Yury Brodskiy. Mission planning and safety assessment for pipeline inspection using autonomous underwater vehicles: A framework based on behavior trees. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04045, 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2402.04045.

- [6] Murat Bakirci. Smart city air quality management through leveraging drones for precision monitoring. Sustainable Cities and Society, 106:105390, 2024.

- [7] Cristian Cataldo-Díaz, Rodrigo Linfati, and John Willmer Escobar. Mathematical models for the electric vehicle routing problem with time windows considering different aspects of the charging process. Annals of Operations Research, 2023. doi:10.1007/s10479-023-05713-z.

- [8] Long Chen, Guangrui Liu, Xia Zhu, and Xin Li. A heuristic routing algorithm for heterogeneous UAVs in time-constrained mec systems. In IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), 2024.

- [9] Jean-François Cordeau and Gilbert Laporte. Models and algorithms for the dynamic dial-a-ride problem. Transportation Science, 43(2):86–99, 2009.

- [10] Jiong Dong, Kaoru Ota, and Mianxiong Dong. UAV-based real-time survivor detection system in post-disaster search and rescue operations. IEEE Journal on Miniaturization for Air and Space Systems, 2(4):209–219, 2021.

- [11] R Ebrahim, MM Bruwer, and SJ Andersen. Small-city traffic management using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). In Proceedings of the Southern African Transport Conference. Southern African Transport Conference 2021, 2021.

- [12] Boris Galkin, Jacek Kibilda, and Luiz A. DaSilva. Coverage analysis for low-altitude uav networks in urban environments. In GLOBECOM 2017 - 2017 IEEE Global Communications Conference, pages 1–6, 2017. doi:10.1109/GLOCOM.2017.8254658.

- [13] IBM. Ibm ilog cplex optimization studio. Online Resource, 2024.

- [14] Ya-Hui Jia, Yi Mei, and Mengjie Zhang. A bilevel ant colony optimization algorithm for capacitated electric vehicle routing problem. IEEE transactions on cybernetics, 52(10):10855–10868, 2021. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2021.3069942.

- [15] Merve Keskin and Bülent Çatay. Partial recharge strategies for the electric vehicle routing problem with time windows. Transportation research part C: emerging technologies, 65:111–127, 2016.

- [16] Navid Ali Khan, NZ Jhanjhi, Sarfraz Nawaz Brohi, Raja Sher Afgun Usmani, and Anand Nayyar. Smart traffic monitoring system using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Computer Communications, 157:434–443, 2020. doi:10.1016/J.COMCOM.2020.04.049.

- [17] Jay Lee, Behrad Bagheri, and Hung-An Kao. A cyber-physical systems architecture for industry 4.0-based manufacturing systems. Manufacturing Letters, 3:18–23, 2015.

- [18] M. Anwar Ma’sum, M. Kholid Arrofi, Grafika Jati, Futuhal Arifin, M. Nanda Kurniawan, Petrus Mursanto, and Wisnu Jatmiko. Simulation of intelligent unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) for military surveillance. In 2013 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems (ICACSIS), pages 161–166, 2013.

- [19] Alejandro Montoya, Christelle Guéret, Jorge E. Mendoza, and Juan G. Villegas. The electric vehicle routing problem with nonlinear charging function. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 103:87–110, 2017. doi:10.1016/j.trb.2017.02.004.

- [20] Robin R. Murphy, Jennifer Kravitz, Scott Stover, and Rahmat A. Shoureshi. Mobile robots in mine rescue and recovery. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2008 International Conference on Technologies for Homeland Security, pages 294–299, 2008.

- [21] Pawel Olejnik, Martin Nowak, and Cezary Zieliński. Wind impact on UAVs: Experimental study using a multi-fan low-speed wind system. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.12345, 2022. arXiv:2207.12345.

- [22] Jane Pauline Ramirez and Salua Hamaza. Multimodal locomotion: Next generation aerial–terrestrial mobile robotics. Advanced Intelligent Systems, 5(1):2300327, 2023.

- [23] Thomas Stastny and Roland Siegwart. Nonlinear guidance for fixed-wing UAVs in strong wind conditions. In 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), pages 4380–4387. IEEE, 2019. doi:10.1109/IROS40897.2019.8967814.

- [24] Paolo Toth and Daniele Vigo. The vehicle routing problem: latest advances and new challenges. Springer, 2007.

- [25] Parthasarathy Velusamy, Santhosh Rajendran, Rakesh Kumar Mahendran, Salman Naseer, Muhammad Shafiq, and Jin-Ghoo Choi. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) in precision agriculture: Applications and challenges. Energies, 15(1):217, 2021.

- [26] Zhaohui Yang, Cunhua Pan, Kezhi Wang, and Mohammad Shikh-Bahaei. Energy efficient resource allocation in UAV-enabled mobile edge computing networks. In IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), 2020.

- [27] Zhe Yu, Yanmin Gong, Shimin Gong, and Yuanxiong Guo. Joint task offloading and resource allocation in UAV-enabled mobile edge computing. In IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), 2020.

- [28] Yong Zeng, Xiaoli Xu, and Rui Zhang. Trajectory design for completion time minimization in uav-enabled multicasting. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 17(4):2233–2246, 2018. doi:10.1109/TWC.2018.2790401.

- [29] Yong Zeng, Rui Zhang, and Teng Joon Lim. Throughput maximization for UAV-enabled mobile relaying systems. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 64(12):4983–4996, 2016. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2016.2611512.

- [30] Chunhua Zhang and John M. Kovacs. The application of small unmanned aerial systems for precision agriculture: a review. Precision Agriculture, 13(6):693–712, 2012.

- [31] Xiao Zhang and Lingjie Duan. Fast deployment of UAV networks for optimal wireless coverage. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 18(3):588–601, 2019. doi:10.1109/TMC.2018.2840143.

- [32] Xiaohui Zhou, Jing Guo, Salman Durrani, and Halim Yanikomeroglu. Uplink coverage performance of an underlay drone cell for temporary events. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), pages 1–6, 2018. doi:10.1109/ICCW.2018.8403634.