Period Assignment for Real-Time Cascade Control Tasks Under Stability and Schedulability Constraints

Abstract

Existing results for cyber-physical systems have been proposed to merge the requirements associated to the stability of the physical components and the schedulability of the cyber components. Nevertheless, none of the existing results has studied these requirements for multiple real-time cascade control tasks where their periods choice are dependent and affect stability. In this paper, we propose a methodology to evaluate the periods of the real-time cascade control tasks that ensures stability of the physical components, then we present a co-design problem for the period choice that guarantees good performance of the physical components and schedulability of the cyber components under fixed-priority scheduling. We then evaluate this methodology on a real use-case of a drone system. Results show the importance of studying these requirements together as their relation has an impact on stable periods range.

Keywords and phrases:

Real-time Systems, Cascade Control, Physical Stability, Control PerformanceCopyright and License:

2012 ACM Subject Classification:

Computer systems organization Embedded and cyber-physical systems ; Computer systems organization Real-time systems ; Computing methodologies Model development and analysisFunding:

This work is, partially, funded by FR ANR France Relance 2030 Mach 2 project, FR ANRT CIFRE StatInf-INRIA grant, FR INRIA ADT KDBench project, FR PSPC STARTEC project and FR INRIA Kepler Associated Team.Editors:

Renato MancusoSeries and Publisher:

Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik

Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik

1 Introduction

Our every day life is improved by the presence of “a new generation of systems with integrated computational and physical capabilities that can interact with humans through many new modalities” [4]. These systems are called cyber-physical systems (CPSs). A defibrillator, a mobile phone, an autonomous car or an aircraft, are all examples of CPSs. Beside constraints like power consumption, security, correctness, size and weight, CPSs may have cyber components required to fulfill their program computations within a limited amount of time, the program is then called real-time task. A real-time task (or simply task) is a recurring program, meaning that consecutive releases of the same program are separated by a predefined time interval. Each release is then referred to as a job, and outputs of the jobs may differ depending on the input received at the start of each job instance. Real-time tasks must meet stringent timing requirements, often imposed by the physical environment, which are also known as real-time constraints. In this paper, a real-time constraint is considered as met by a task if its worst-case response time (WCRT) is always smaller than the minimal inter-arrival time between two jobs. The worst-case response time is the largest time elapsed from the beginning of the job’s execution until its end (including preemptions, suspensions, etc).

Concretely, the CPS design implies the implementation of controller programs as periodic tasks that have real-time constraints to meet. More precisely we understand by controller, a cyber component algorithm deciding what actions must be taken based on sensor readings or other input data. The output of the controller is the input to the physical component of the system, usually called plant, which forces the output of the plant to follow a desired setpoint [6]. This implies that a control task implements the controller’s algorithm, such that computing the output of the controller program is done within this task. Moreover, by stability we mean that the output of the CPS is under control, following the desired setpoint in the presence of external perturbations.

Usually, the controller programs are modeled as real-time tasks and the associated CPS task model [10] is considered more general than the classical real-time task model as defined by Liu and Layland in [13]. Recent results [5] have underlined that there is a gap between the CPS stability as defined within a control theory context and the schedulability as defined within the real-time scheduling community and the authors have proposed a new model to fill this gap. Nevertheless, the problem of having multiple control dependent tasks has not been studied from a control scheduling co-design perspective. Often, the real-time community has studied the impact of the period variation on the stability of one controller. To the best of our knowledge, no result has been presented for the stability of a system with multiple real-time cascade control tasks. Real-time cascade control tasks represent multiple control tasks concatenated together, where the output of one control task is the input of the other.

Our contribution: In this paper, we investigate the stability of the cascade control system in order to derive an interval of periods upon which the system is stable. Then we propose an optimization problem to choose the proper values of periods from the stable region based on the control performance and system utilization. We then evaluate our methodology for drone dynamics inspired by a real use-case.

Organisation of the paper: The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we present existing results that combine control and scheduling requirements. In Section 3, we present the real-time and control system descriptions along with the proposed co-design problem formulation. In Section 4, we describe the methodology to analyse the stability of the system and derive stable regions of periods. In Section 5, we present a bound on the number of allowable deadline misses for a control task based on the stability region. In Section 6, we define the use-case used in our study, and then evaluate our methodology in Section 7. In Section 8 we present interesting observations noted during the evaluation phase and we conclude in Section 9.

2 Control-Scheduling State of the Art

2.1 Scheduling and Control Co-Design

Many studies have been dedicated to the control-scheduling co-design problem. An early result [21] considers the optimization of global system performance using control performance index and subject to computing resources constraints. In [18], authors present an approach to optimize end-to-end timing constraints subject to performance and schedulability constraints of a real-time control system. Here periods of control tasks are modified to satisfy the objective of minimizing systems utilization while respecting the performance requirements. In [20], authors follow the same approach while considering the real-time control system subject to communication delays. [24, 25] targeted the control scheduling co-design, where the assignment of periods and priorities of multiple control applications running on the same processor is done considering some control performance metrics. Authors of [2] consider the effect of delays and jitter on the system stability and provided an approach for period assignment and scheduling scheme to guarantee stability. In [1], authors consider the problem of synthesizing timing contracts that guarantee stability and schedulability. All mentioned results considered hard-deadlines, meaning each task is required to meet all deadlines. In reality, control tasks could allow some relaxation of this constraint by allowing some deadline misses, while periods are chosen, often, as multiples of sensor periods leading to harmonic rates [22].

2.2 Fault Tolerant Control System

The relaxation of hard deadline requirements for real-time control systems is, also, considered in the literature. It is shown that the stability of control systems is not only dependent on the system dynamics and choice of periods, but also the stability depends on the number of consecutive deadline misses that the control task encounters. In [23], authors analyze stability and performance of control systems subject to burst of deadline misses, and show that stability analysis alone is not sufficient to properly quantify robustness regarding deadline misses. In [16], authors propose an adaptive control design to handle the sporadic overloads to counteract the effect on stability and performance. In [10], authors propose a new periodic fault-tolerant CPS task model, which generalize the existing task models. But also the model captures the stability and efficiency of the CPS by capturing tolerable number of control update misses. In this scheduling scheme tasks periods are considered as given.

Authors in [5] propose a first method to combine both previously mentioned working paths. This is done by proposing a model to jointly determine tasks periods and manage deadline misses. In their paper, a stable region of the physical system is presented, each point in this region corresponds to a pair of period and number of allowed consecutive deadline misses. This means in their proposed model to know that a control task can tolerate a certain number of consecutive deadline misses, its period could be chosen between a minimum and a maximum value based on the stability region.

To the best of our knowledge, no other result has been proposed to the co-design problem when the system is composed of multiple dependent control tasks in a cascade structure. So, there is no result on the effect of the dependence between control tasks on the region of stable periods and how do we quantify the maximum number of allowable deadline misses based on the region of stability.

3 Problem Definition

3.1 Real-time Model

We consider a task system of synchronous implicit deadline periodic tasks scheduled according to a preemptive fixed-priority scheduling policy on one processor . The tasks are ordered according to their priority. A task has a higher priority than a task when . The priority assignment is given and finding such assignment is beyond the purpose of this paper. A task is defined by , its worst-case execution time, its minimal inter-arrival time or period and , its deadline with . We denote by its utilization and the total utilization of the task system is denoted by . We assume that all tasks are released for the first time synchronously at .

3.2 Cascade Control Model

A control system regulates or controls the behaviour of other devices or systems using control loops [7, 3, 11, 15]. There are, mainly, two types of control systems, open-loop and closed-loop control. Closed-loop control systems (also known as feedback control systems) have been the first examples of hard real-time systems [23]. In this paper, we deal with closed-loop control systems.

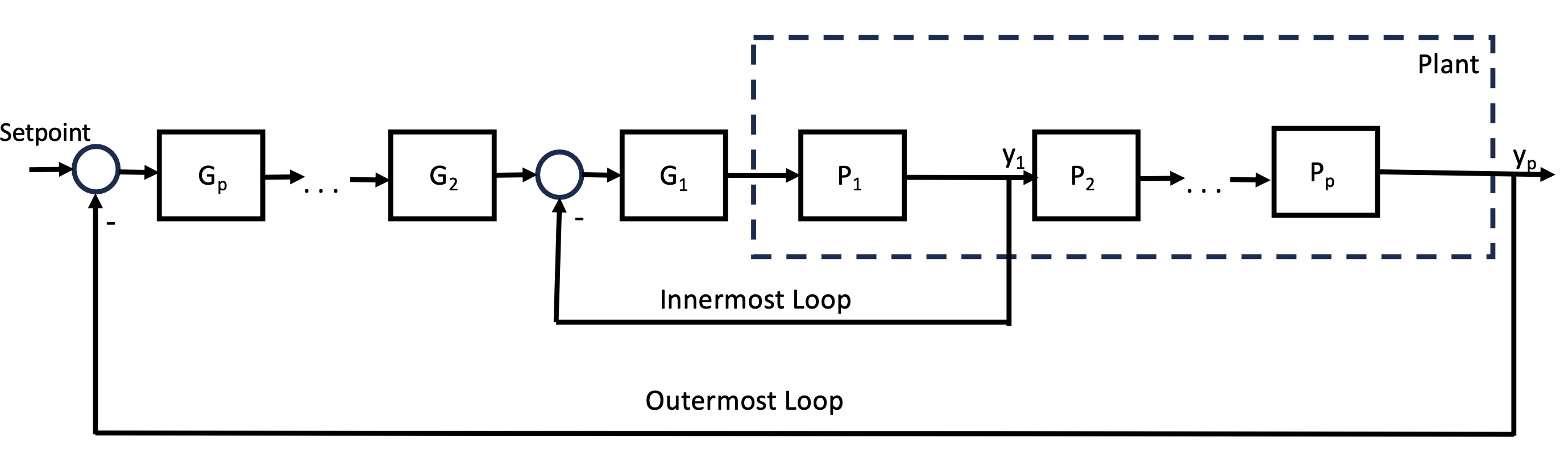

Cascade closed-loop control is the use of multiple control loops to control the behaviour of a system. In Figure 1, we illustrate cascade loops each containing a controller and a plant . In a cascade control system, the output of the outer loop controller is the setpoint to the inner loop controller . In addition, is faster than allowing the inner loop to react rapidly to fast changing dynamics which reduce the error of the outer loop.

Stability

A control system is said stable if its output is bounded for a given bounded input. For instance, in Figure 1 for a bounded input of controller , a bounded output is expected. The stability of a cascade control is studied in order to derive a stability region as a function of the sampling period of each controller. That is for a controller we derive a range of periods for in an interval , such that any period value in this interval ensures stability of the system. Several methods exist to identify such interval and in this paper, we use the Jury’s stability [17] (see more details in Section 4).

Control Performance

When it comes to control tasks, we evaluate the performance of the closed-loop system since the stability itself does not guaranty the optimal behaviour of the system. Usually, the control performance is defined in terms of a cost function that is evaluated during the run-time of the controller. In this paper, we define the performance as the cost defined by the integral of time absolute error (ITAE) [8]:

| (1) |

Where is the system error between the desired output (setpoint) and the measured output. This is not the unique way to define the control cost, other formulations exist such as the Integral of squared error (ISE) or integral of absolute error (IAE). As stated in [19], ITAE has the advantage of producing smaller overshoots and oscillations than ISE and IAE. In addition, ITAE has the selectivity needed for a good metric meaning a minimum value could be captured when system parameters are varied. A large value of the cost indicates a low control performance, meaning that there is a large deviation from the desired setpoint. The cost depends also on the sampling period, the more frequent sampling of control tasks is, the smaller is the error leading to a lower (better) cost.

3.3 Co-design Problem

The co-design problem is defined as the problem where the stability and the schedulability meet with the objective of finding a compromise solution for each of them. From a stability and performance point of view, one wants the control tasks to have the smallest possible periods, while this might overload the system from a scheduling point of view. So, the co-design problem requires a solution optimizing the control performance represented by Equation 1, while respecting stability and schedulability guarantees. Then, we define the optimization problem as follows:

| (2) |

For the control performance we choose sampling periods that decrease the control cost as much as possible. These periods should be chosen within the interval which ensures the stability of the physical system. Our solution to compute this interval is described in Section 4. Also, the period of the inner loop should be smaller than that of the outer loop to reduce overall system error, where in the third condition corresponds to the inner loop and to the outer loop. Moreover, from scheduling point of view we chose periods that guarantee there is no violation of the sufficient condition of schedulability according to a fixed priority scheduling algorithm with the total utilization lower than .

This bound is introduced in [13] as follows:

For a set of tasks scheduled with fixed priority, and the restriction that

the ratio between any two request periods is less than , the least upper bound to the

processor utilization factor is .

For evaluation purposes and when , , since is a decreasing function with respect to the number of tasks, then for any number of tasks is a sufficient bound [13].

3.4 Example

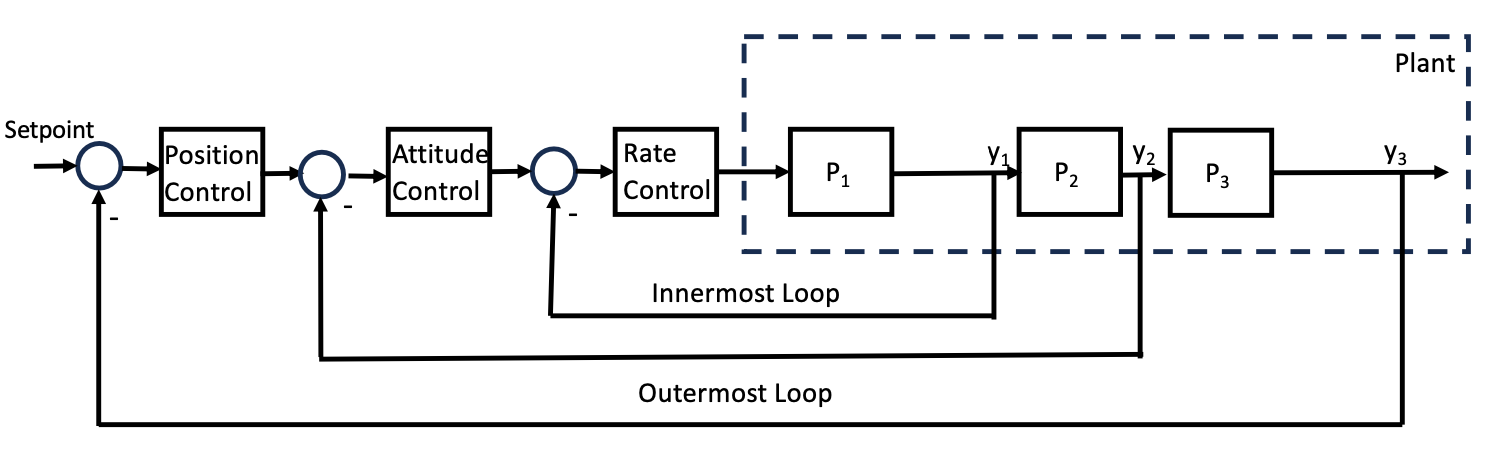

To illustrate our definitions and results, we consider an example of tasks set with tasks ordered according to their priorities associated to the use-case described in Section 6. A task has a higher priority than a task when . Tasks are scheduled on one processor according to a preemptive fixed priority scheduling algorithm. Their parameters are described in Table 1. The worst-case execution time is obtained as the largest observed execution time during minutes of functioning for the associated use-case. The task system contains tasks, of which are control tasks. The relation between control tasks is described by cascade control loops in Figure 2. As for non-control tasks, we do not present them in Figure 2 because we consider that the output of the plant is complete and no data could be missed. Whereas in real implementation we use sensors to capture the behaviour of the system, in this case data should be estimated, filtered and corrected and this is the difference between real implementation and simulations.

| Task index | Task name | (ms) | (ms) | Control task |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensors | 10 | 0.761 | Non | |

| EKF2 | 10 | 5.315 | Non | |

| Hover trust | 15 | 0.114 | Non | |

| Navigator | 25 | 1.365 | Non | |

| Position control | 15 | 0.236 | Yes | |

| Flight manager | 15 | 0.511 | Non | |

| Attitude control | 15 | 0.138 | Yes | |

| Commander | 50 | 0.266 | Non | |

| Rate control | 15 | 0.17 | Yes |

4 Stability Analysis

When designing and analysing such system the inner-most loop should be treated first, then the loop that generates the setpoint of the inner-most loop until we reach the outer-most loop. To study the stability region of the system with respect to the sampling periods of the cascade controller, we represent the dynamics of the system using a linear transfer function representation. Afterwards, we discretize this transfer function with respect to the sampling period .

4.1 Closed-loop

Plants of real applications are non-linear, but for control design purposes usually the plant dynamics are linearized around an operation point. For our general stability analysis we consider two plants and described by transfer functions of the general form:

| (3) |

where , and are constants derived from the dynamics of the physical plant as described in Section 6.1 (see Equation 14).

The controllers and are assumed to be PID controller and its general transfer function is as follows:

| (4) |

Forward discretization

To introduce the sampling period we discretize the equations of the plants and the controllers to transfer them from continuous-time to discrete-time. We do this by replacing the Laplace variable with an approximation using the forward Euler method:

where is the sampling period and is the forward time shift.

Combining the dynamics and the controller descriptions from equations 3 and 4 is used to study of the stability of the closed-loop as follows:

| (5) |

where and are the sampling periods of the inner and outer loops, respectively. It is to be noted that the outer loop depends on the parameters of the inner loop, so that the closed-loop transfer function of the would depend on its period and the period of . If several loops exist, then this procedure is generalized to obtain the closed-loop transfer functions.

4.2 Jury’s stability

Jury’s stability is a criterion for discrete-time systems that is applied to the characteristic equations that are a function of to check there stability. Characteristic equation is the denominator of the closed-loop transfer function. Assuming a general characteristic equation of the form:

| (6) |

Jury’s stability provides necessary and sufficient conditions to ensure that has no roots outside the unit circle.

Necessary condition for stability.

For the sufficient conditions we construct the Jury table first, then check the conditions.

where each row is build based on the previous one as follows:

Sufficient condition for stability.

To ensure stability, the following conditions must be satisfied:

| (7) |

If any of these conditions fail, the system is unstable.

From these conditions, we solve the characteristic equation of the closed-loop transfer functions in Equation 5 to determine the ranges of and which keeping the system stable. Assuming all parameters other than the periods are given, the coefficients of the characteristic equation 6 () are dependent on the periods only. This means, conditions of stability in Equation 7 could be solved to bound the values of ensuring that the system is stable, leading to the stability interval.

We present in the flow chart of Figure 3 the procedure of deriving all stable periods of a system with 2 real-time cascade control tasks (for the sake of the simplicity, we present it for loops but it is generalizable to loops) . First, we fix the physical system parameters and controller parameters. We assume that the system at hand has at least a set of parameters where a value of and exists. Then we solve for the inner-most loop the Jury’s conditions seen before to derive the interval of periods that are stable. If we did not succeed to find a solution then we go back and change the controller parameters. When a solution is found we then proceed to analyse the next loop. Now we know that the transfer function of the outer loop will depend on both and , so to solve for we fix a value of we do so by looping over all values in the stable interval we derived in the previous step. After fixing the only variable now is the period and we solve again the jury’s conditions to obtain the stable values of . After looping over all values of in the stable interval, we obtain the combinations of and that make the overall system stable.

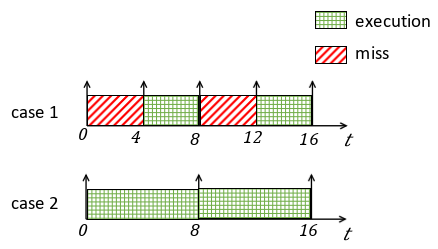

5 Allowable deadline miss

A control system remains stable in the presence of a maximum number of consecutive deadline misses, where the value of depends on the dynamics of the controlled system (see Section 2.2). We understand by missing a deadline that each time a job does not complete its execution, the system uses data from the last previously completed job. Even if the system is stable for consecutive deadline misses this may impact the performance of the system. Since the best performance is achieved when updating the control as frequent as possible, the presence of deadline miss reduce the control performance. If a job of a control task misses consecutive deadlines, this is equivalent to say that we execute with a period . This reasoning allows us to propose the following result.

Theorem 1.

In a task system , a control task with a period within a region of stable periods keeps the system stable if it is subject up to a maximum number of consecutive deadline misses is equal to:

| (8) |

while all other tasks meet their deadlines.

Proof.

From the stability point of view , and we know that the system is stable for any then the system is stable for .

Example 2.

Looking at the example of Figure 4, Case depicts a control task running with a period of we have one control update miss followed by a correct execution and control update. Thus, we get a new data every , which is equivalent to Case where we see a control task running with a period of and successfully completing its execution every time. Knowing that the system is stable for Case with a control update each , we can then say for a control period of the system remains stable if we miss a single control update.

6 Drone Autopilot Use-Case

We provide a use-case using the set of tasks associated to an existing autopilot, PX4 111https://px4.io/software/software-overview/ modified to integrate periodic arrivals. The tasks or programs are executed on a real execution platform Pixhawk composed of a microcontroller (a single core ARM Cortex-M4), sensors and actuators.

From those executions, we consider for each program a 4-tuple (, , , ) composed by a program , a microcontroller , a measurement protocol and an ordered sequence of execution times of program on the microcontroller . For the program , one provides the source code as well as the binary code. A measurement protocol is defined by the variation of the input variables (associated to sensors) of these benchmarks. In our case, the variation of the input variables is obtained by collecting them during a simulated flight of a drone within a Gazebo simulation environment. The fourth element is an ordered set of execution times, , proposed to overcome the difficulty of the reproducibility of results while comparing execution times measured for the same program on slightly different microcontroller configurations. Moreover, we use execution times measured at the scheduler level in order to decrease the intrusion of the measurement protocol. Such measurements are said to be obtained in a hardware-in-the-loop manner. We understand by hardware-in-the-loop that the execution of the benchmarks is done on a microcontroller while sensors and actuators of a real-time system, as well as its physical environment, are simulated.

Among the programs of the PX4 Figure 5, three are the control tasks Position Control, Attitude Control and Rate Control. These control tasks form three cascaded loops controlling the overall position of the drone (see more details in Section 3.4).

6.1 Drone dynamics

A first step to control design or stability analysis of any control system is to derive its dynamics representation. As seen in the use-case the targeted system is a drone, so we start with a general drone representation. The dynamics of the drone consists of two parts translational dynamics and rotational dynamics. The dynamics could be derived from the physical laws and has been exhaustively studied in control theory.

It follows from [12, 26], that the dynamics of the drone should be studied with respect to two coordinates, earth coordinate which is the general one and drone body coordinate which is fixed to the drone body and moves with it.

The translational position of the drone is studied with respect to the body frame, then transformed into the earth frame using a transformation matrix. Then we get the translational acceleration of the drone as follows:

| (9) |

Similarly the rotational position is also first derived in the body frame of the drone and then transformed to the earth frame. Here we present the angular velocity and acceleration of drone around axis under body frame. Where as the roll, pitch and yaw: are angular velocity and angular acceleration of drone in the earth frame:

| (10) |

| (11) |

Generally the movement of the drone is controlled by varying the speed of its propellers. Here we represent the control outputs in terms of and the thrust and drag coefficients, and the propeller speed. The would then be computed by the control tasks, and the propeller speeds would have to be calculated from them for a real implementation.

| (12) |

As could be noticed from the model the system is a nonlinear one. So for the design of the controller and stability analysis, we linearize the equations presented above. From [26] the linearized equations are as follows:

| (13) |

In order to reproduce a similar behavior to the PX4 autopilot, we aim to analyse three controllers:

-

Position Control which controls both position and velocity of the translational motion and respectively.

-

Attitude Control which controls the angular velocity of the drone .

-

Rate Control which controls the angular acceleration .

Starting from the inner-most loop, which is the Rate Control, this controller takes as input setpoint the targeted angular acceleration values provided by the Attitude Control. The inner-most loop transfer functions from the linearized equations 13 also called the open-loop transfer functions are:

| (14) |

These three angular rates have similar dynamics, so we will do the representation for one of them. So, for one of the dynamics of Equation 14, the closed-loop equation becomes:

| (15) |

Now discretizing this equation as seen in Section 4.1 we obtain the following discrete closed-loop transfer function:

| (16) |

As a reminder, we have seen that the outer loop depends on the parameters of the inner loop, so that the closed-loop transfer function of the Attitude Control would depend on its period and the period of the Rate Control and so on. Then the closed-loop transfer functions of Attitude Control and Position Control could be represented as follows:

| (17) |

7 Evaluation

For our evaluation we consider the PX4 dynamics as explained Section 6. We start by assuming the system parameters to be as depicted in Tables 2 and 3.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moment of inertia around y-axis | 0.03 | ||

| Distance from propeller to drone center | 0.25 | m | |

| Mass of the drone | 1.5 | Kg |

| Controller | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| rate controller | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.003 |

| angle controller | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Velocity controller | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Position controller | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

7.1 Stability Analysis

We implement the dynamics represented in equations 16 and 17, and the procedure of extracting the stability regions for the control tasks periods depicted in Figure 3 by using Maple 222Maple [14] is a powerful computer algebra system used for symbolic computation and mathematical modeling.. We present the results of this analysis in Figure 6, where the blue regions are the period combinations that make the physical system stable. We see that the periods and of the Rate Control and Attitude Control reaches a maximum of around , whereas of the Position Control could tolerate a period of for some period combinations. This could be due to the fact that rotational dynamics should be acted upon more frequently than the translational dynamics.

7.2 Performance Evaluation

Evaluating the performance of the control system represented by Equation 1 should be done during the execution of the system. For this we use Simulink [9] to monitor the step response of the system and measure its performance. The performance is done over all the stable combinations of , and . For the ease of representation we fix the value of and plot the variation of the cost with respect to the periods and , the results are depicted in Figure 7. We can notice from the plots that the cost exhibits a general increasing trend as periods increase, the presence of some oscillations could be due to the discretization effect where some periods align better with the system dynamics resulting in lower cost. For this reason we consider the optimization since it is not always guaranteed that the lowest stable periods will result in the best performance.

7.3 Co-design Evaluation

After obtaining the stable periods and their corresponding performances it is time to evaluate the co-design problem presented in Section 2.1. From Table 1 we can see that the total utilization of the PX4 tasks excluding the three control tasks is (non-control utilization), the output of the co-design problem is depicted in Table 4 Case which shows the values of the three periods that keeps the total utilization less than while having a low control cost. In an attempt to see what is the effect of adding more load to the system, we increase the value of to (Case ) and we re-evaluate the co-design problem. Increasing the utilization is equivalent to assuming a multi-objective optimization where we add in the minimization and give it higher weight than the control cost J, this triggers period relaxation while allowing some performance degradation. We see that the periods are more relaxed compared to Case to account for the increased utilization, while we notice that the increase in the cost is not critical this is due to the good choice of controller parameters333More discussion on this in Section 8.2..

| Case | 0.59 | 0.613 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 396.3 |

| Case | 0.68 | 0.6874 | 70 | 75 | 75 | 397.93 |

7.4 Single Control Task

If we implement the controllers into a single program (task), this is equivalent to say that we run the controllers with the same period. To validate the behavior of such case, we check the step response of the system and performance when the period is set to be:

-

(a)

equal to the shortest possible period for the controllers to be stable,

-

(b)

equal to the longest possible period for the controllers to be stable.

We show in Table 5 the performance and total utilization of the two cases. For Case we see that it provides a slightly better performance than the optimal assignment seen in Case of Table 4. But this case wasn’t considered because it violates the condition on the allowable total utilization (). Case shows good total utilization but a slightly higher cost . It could be noticed from the step response of the two cases in Figure 8, that the two responses coincide which ensures that the performance is not changing by much thanks to a good choice of system parameters.

| Case | 0.59 | 0.6988 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 394.5 |

| Case | 0.59 | 0.5968 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 400.13 |

8 Important Observations

8.1 Impact of Cascade

A question that could be asked, why don’t we assign periods to each controller separately as if they were independent from one another? To answer this question we do stability analysis and check if cascaded loop sampling periods impact each other. We start to solve for the period of the inner-most loop, i.e. the Rate Control in our case, by solving the Jury’s conditions as discussed in Section 4. We obtain that the inner-most loop by itself is stable for the values of period in the range to . When we add the second loop, i.e. Attitude Control, we see that these values of are stable for small values of , while for small values of the period of the second loop could reach a value of more than , see Figure 9(a) (red region). After adding the last loop, i.e. Position Control, we notice that the region of stability becomes much more constrained as in Figure 9(a) (blue region). If we zoom on this region, then we obtain Figure 9(b). So, yes there is an important impact of the cascade structure on the sampling period, we’ve seen a drop from to around for and a drop from around to for .

8.2 Impact of Controller Parameters

In this section, we discuss the importance of the controller parameters choice during the first step of the analysis. For this we attempt to change the integral gain of the velocity controller and the proportional gain of the position controller , and repeat the whole process of evaluation we have seen in Section 7. If we compare Case of Table 6 with Case of Table 4, we see that although here the set of optimal periods is lower than that of Case the cost of the control is much higher. This could be seen on the plot of the step response of the two cases Figure 10, where the response converges slowly to the required setpoint whereas response is much faster.

Another observation is that if the controller parameters are badly chosen as in this case, relaxing the periods will lead to much higher cost where we see for Case an increase of in the cost with respect to Case . Whereas when we had good parameters in the previous evaluation relaxing the control tasks periods did not show this drastic impact (Table 4).

| Case | 0.59 | 0.626 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 10276 |

| Case | 0.68 | 0.689 | 50 | 65 | 65 | 14878.16 |

Similarly if we replicate what is done in Section 7.4 for the current parameters we obtain the results in Table 7. Since as we said, the parameters are not chosen correctly in this section the choice of periods impact a lot the performance of the system. This could be seen from Figure 11, more precisely the “Zoomed In” part where we see that the response of Case will eventually converge faster than that of Case .

| Case | 0.59 | 0.6988 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10029.7 |

| Case | 0.59 | 0.6008 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 10579.6 |

9 Conclusion

In this paper we present a methodology to analyse the stability of cascade control system with respect to the sampling periods using Jury’s stability. Then we use these periods to solve a co-design problem resulting in a set of periods for the real-time cascade control tasks, that guarantees a good control performance and a schedulable task set under fixed-priority preemptive scheduling. Our evaluation shows the importance of studying the real-time cascade control tasks together as they have an impact on each other when it comes to period choices and stability. An extension of this work could be the integration of the non-control tasks in the co-design problem, because currently we only consider their contribution to the over all utilization of the system where in fact their periods could also be modified and this might have an impact on the system performance. Another possible extension could be the relaxation of the utilization bound used, which allows a better trade-off between the control performance and the schedulability.

References

- [1] Mohammad Al Khatib, Antoine Girard, and Thao Dang. Scheduling of embedded controllers under timing contracts. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Hybrid Systems: Computation and Control, pages 131–140, 2017. doi:10.1145/3049797.3049816.

- [2] Amir Aminifar, Soheil Samii, Petru Eles, Zebo Peng, and Anton Cervin. Designing high-quality embedded control systems with guaranteed stability. In Proceedings of the 33rd IEEE Real-Time Systems Symposium, RTSS 2012, pages 283–292. IEEE Computer Society, 2012. doi:10.1109/RTSS.2012.79.

- [3] Kagan Koray Ayten, Ahmet Dumlu, Sadrettin Golcugezli, Emre Tusik, and Gurkan Kalınay. Real-time implementation of cascade nonlinear ff-pi retarted controller design for industrial process systems. Preprints, August 2024. doi:10.20944/preprints202408.0288.v1.

- [4] Radhakisan Baheti and Helen Gill. Cyber-physical systems. IEEE, 2011.

- [5] Hoon Sung Chwa, Kang G. Shin, and Jinkyu Lee. Closing the gap between stability and schedulability: A new task model for cyber-physical systems. In IEEE Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium, RTAS, pages 327–337, 2018. doi:10.1109/RTAS.2018.00040.

- [6] John C Doyle, Bruce A Francis, and Allen R Tannenbaum. Feedback control theory. Courier Corporation, 2013.

- [7] RG Franks and CW Worley. Quantitative analysis of cascade control. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry, 48(6):1074–1079, 1956.

- [8] Dunstan Graham and R. C. Lathrop. The synthesis of “optimum” transient response: Criteria and standard forms. Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, Part II: Applications and Industry, 72(5):273–288, 1953. doi:10.1109/TAI.1953.6371346.

- [9] The MathWorks Inc. MATLAB version: 9.11.0 (R2021b). Natick, Massachusetts, United States, 2021. URL: https://www.mathworks.com.

- [10] Jinkyu Lee and Kang G. Shin. Development and use of a new task model for cyber-physical systems: A real-time scheduling perspective. Journal of Systems and Software, 126:45–56, 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2017.01.004.

- [11] Alberto Leva and Federico Terraneo. Teaching task scheduling as multivariable cascade control. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 49(6):280–285, 2016. 11th IFAC Symposium on Advances in Control Education ACE 2016. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2016.07.190.

- [12] Jun Li and Yuntang Li. Dynamic analysis and pid control for a quadrotor. In 2011 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, pages 573–578, 2011. doi:10.1109/ICMA.2011.5985724.

- [13] Chung Laung Liu and James W. Layland. Scheduling algorithms for multiprogramming in a hard-real-time environment. J. ACM, 20(1):46–61, 1973. doi:10.1145/321738.321743.

- [14] Maplesoft, a division of Waterloo Maple Inc. Maple User Manual, 1996-2023. Version range: 1996–2023.

- [15] N. A. Patil and G.V. Lakhekar. Design of pid controller for cascade control process using genetic algorithm. In 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), pages 1089–1095, 2017. doi:10.1109/ICCONS.2017.8250634.

- [16] Paolo Pazzaglia, Arne Hamann, Dirk Ziegenbein, and Martina Maggio. Adaptive design of real-time control systems subject to sporadic overruns. In 2021 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), pages 1887–1892. IEEE, 2021. doi:10.23919/DATE51398.2021.9473913.

- [17] Karl J. Åström and Björn Wittenmark. Computer-controlled systems (3rd ed.). Prentice-Hall, Inc., USA, 1997.

- [18] Minsoo Ryu, Seongsoo Hong, and Manas Saksena. Streamlinig real-time controller design: From performance specifications to end-to-end timing constraints. In Proceedings Third IEEE Real-Time Technology and Applications Symposium, pages 91–99, July 1997. doi:10.1109/RTTAS.1997.601347.

- [19] W. C. Schultz and V. C. Rideout. Control system performance measures: Past, present, and future. IRE Transactions on Automatic Control, AC-6(1):22–35, 1961. doi:10.1109/TAC.1961.6429306.

- [20] O. Sename, D. Simon, and D. Robert. Feedback scheduling for real-time control of systems with communication delays. In EFTA 2003. 2003 IEEE Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation. Proceedings (Cat. No.03TH8696), volume 2, pages 454–461 vol.2, 2003. doi:10.1109/ETFA.2003.1248734.

- [21] D. Seto, J.P. Lehoczky, L. Sha, and K.G. Shin. On task schedulability in real-time control systems. In 17th IEEE Real-Time Systems Symposium, pages 13–21, 1996. doi:10.1109/REAL.1996.563693.

- [22] Marion Sudvarg, Ao Li, Daisy Wang, Sanjoy K. Baruah, Jeremy Buhler, Chris Gill, Ning Zhang, and Pontus Ekberg. Elastic scheduling for harmonic task systems. In 30th IEEE Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium, RTAS, pages 334–347. IEEE, 2024. doi:10.1109/RTAS61025.2024.00034.

- [23] Nils Vreman, Anton Cervin, and Martina Maggio. Stability and Performance Analysis of Control Systems Subject to Bursts of Deadline Misses. In 33rd Euromicro Conference on Real-Time Systems (ECRTS 2021), volume 196, pages 15:1–15:23, 2021. doi:10.4230/LIPICS.ECRTS.2021.15.

- [24] Yang Xu, Anton Cervin, and Karl-Erik Årzén. Jitter-robust lqg control and real-time scheduling co-design. In 2018 annual American control conference (ACC), pages 3189–3196. IEEE, 2018. doi:10.23919/ACC.2018.8430953.

- [25] Yang Xu, Karl-Erik Årzén, Anton Cervin, Enrico Bini, and Bogdan Tanasa. Exploiting job response-time information in the co-design of real-time control systems. In 2015 IEEE 21st International Conference on Embedded and Real-Time Computing Systems and Applications, pages 247–256, 2015. doi:10.1109/RTCSA.2015.23.

- [26] Runjiang Zhao. Inner/outer-loop control of a drone under disturbances and uncertainties: a sliding mode control approach. Master’s thesis, Northeastern University, 2020. doi:10.17760/D20382857.