DAMA: A Dual Arbitration Mechanism for Mixed-Criticality Applications

Abstract

We discuss hardware resource management in mixed-criticality systems, where requestors may issue latency-critical () and non-latency-critical () requests. requests must adhere to strict latency bounds imposed by safety-critical applications, but timely servicing requests is necessary to maximize overall system performance in the average case. In this paper, we address this tradeoff for a shared memory resource by proposing DAMA, a dual arbitration mechanism that imposes an upper bound on the cumulative latency of requests without unduly impacting performance. DAMA comprises a high-performance arbiter, a real-time arbiter, and a mechanism that constantly monitors the cumulative latency of requests suffered by each requestor. DAMA primarily executes in high-performance mode and only switches to real-time mode in the rare instances when its incorporated mechanism detects a violation of a task’s timing guarantee. We demonstrate the effectiveness of our arbitration scheme by adapting a predictable prefetcher that issues requests and attaching it to the L1 caches of our cores. We show both formally and experimentally that DAMA provides timing guarantees for requests while processing other requests. We also demonstrate that with a negligible overhead of less than 1.5% on the cumulative latency bound of requests, DAMA can achieve an equivalent average performance to a prefetcher that processes requests under a high-performance arbitration scheme.

Keywords and phrases:

Real-time Systems, Mixed-criticality Applications, Memory controllers, PrefetchersCopyright and License:

2012 ACM Subject Classification:

Computer systems organization Real-time system architectureSupplementary Material:

Software (Source Code): https://github.com/wlawand99/gem5/tree/pred-prefetcher [1]archived at

swh:1:dir:090ec54b40c15efe635df04b81d49a4e607ef6da

swh:1:dir:090ec54b40c15efe635df04b81d49a4e607ef6da

Funding:

This work has been supported by NSERC. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsor.Editors:

Renato MancusoSeries and Publisher:

Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik

Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik

1 Introduction

The growing demand to execute multiple complex workloads with varying criticalities has driven the adoption of multicore platforms with advanced features in real-time systems. A common way of categorizing tasks in such systems is based on their safety-criticality. High-criticality tasks require stringent worst-case execution time (WCET) guarantees. Such guarantees depends on the latency of memory requests issued by hardware components used to execute the tasks, e.g. requests generated by a core following L1 misses. We name the requests that affect the WCET of a high-criticality task as latency-critical requests (). Additionally, hardware components issue other, non-latency-critical () requests that affect the average execution time of both high-criticality and low-criticality tasks. Although adopting multicore architectures offers significant computational benefits, they also introduce substantial challenges from a real-time perspective. These challenges arise from two factors: resource contention between and requests in multicore systems, and the unpredictable behavior of advanced features that alter the resource state. Such challenges complicate the system analysis and make it difficult to provide timing guarantees for requests. As a result, a tradeoff arises between performance and predictability, where promptly servicing requests can improve the overall system performance, but can potentially violate the latency bounds of requests.

Previous works that aim to provide timing guarantees for memory requests have tackled this tradeoff in mixed-criticality systems by regulating the bandwidth of the memory resource [46],[47], or by delivering differentiated services for requests based on criticality [17, 11, 22, 15, 18]. Prior work has also addressed this tradeoff at the memory arbiter level by introducing a dual arbitration model called Duetto[31, 32, 33]. This scheme utilizes a high-performance arbiter (HPA) to maximize throughput until a timing violation is detected by monitoring the state of the memory resource. When a violation occurs, the system transitions to a real-time arbiter (RTA) to enforce a strict latency bound on a per-request basis. Although this mechanism is provably safe, providing a bound on a per-request basis is complex: the approach must recompute the remaining request latency every clock cycle based on the state of the resource and request queues.

In this paper, we propose DAMA, a novel dual arbitration mechanism. Our key insight is that the WCET guarantee for high-criticality task depends on the cumulative latency of requests [26, 19, 31, 32, 33]. Hence, instead of the per-request bound provided by Duetto, DAMA offers a bound on the cumulative request latency. This enables the use of a simpler monitoring mechanism which can further incorporate both and requests in a more flexible and performant way. In high-performance mode, all and requests are given equal priority to maximize performance. In contrast, in real-time mode, only requests are considered to maintain their latency bounds. In details, our contributions are:

-

1.

We introduce and discuss the DAMA model in Section 3. DAMA maintains a set of latency counters, which track the accumulated latency slack by each requestor at run-time in a simple and efficient manner. By bounding the maximum value of the counters, we formally show that DAMA provides a guarantee on the cumulative latency of requests issued by a task.

-

2.

We show how DAMA can incorporate requests by integrating a predictable prefetcher in Section 4. We maintain cache analyzability using a similar approach to [13], where a prefetch side buffer is employed to avoid altering the cache state. Contrary to [13], we consider a prefetcher attached to the L1 data cache, which is more efficient [34] but requires careful management of and requests issued by the same core.

- 3.

2 Related Work and Background

2.1 Latency Regulation Mechanisms

Modern commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) systems aim to maximize average performance by employing high-performance arbiters that adopt different policies such as FCFS policy[21], parallelism-aware batch policy [35], out-of-order policy [38], and many more. While these arbitration schemes significantly improve average performance, they fail to honor the timing requirements for requests in a system.

To address this, extensive research has focused on designing predictable arbiters, such as round-robin (RR) and its various adaptations [25], time division multiplexing (TDM) [20], and similar approaches. These arbiters are designed to provide timing guarantees, making them suitable for real-time applications. While this approach provides strong timing guarantees, it can lead to substantial overall performance degradation due to its rigid scheduling policy.

Many studies have addressed the tradeoff between predictability and average performance by handling requests with varying levels of criticality. One line of work has focused on proposing OS-level mechanisms to manage the memory resource primarily through space isolation and bandwidth regulation in memory resources [27, 45, 46]. Another significant body of work has explored redesigning the memory controllers to support mixed-criticality systems, offering differentiated services to critical and non-critical requests [17, 11, 22, 15, 18]. The work most related to ours is the Duetto model [31], which combines the performance benefits of high-performance arbiters with bounded request latency. Duetto associates a relative deadline (maximum per-request latency) to each requestor and uses it to derive an absolute deadline for each request at runtime. It then uses a monitoring component to dynamically compute the worst-case finish time of the request, assuming that the system continues to operate in high-performance mode for the current clock cycle. If the computed finish time exceeds the deadline, Duetto switches to a real-time arbiter to preserve the per-request latency guarantee. This arbitration scheme has been applied to a banked SRAM model in [31], to a DRAM model in [32], and to a coherent shared cache in [33]. DAMA simplifies the Duetto model by avoiding tracking and computing individual per-request latencies, and instead providing a cumulative latency bounds on all requests issued by a task. As discussed in Section 5.4, this results in better performance for the same task-level latency bound, and a potentially easier hardware implementation.

2.2 Prefetchers

Prefetching is a commonly used technique that hides memory latency by anticipating future memory accesses and proactively loading data into the cache before the processor requests it. This has proven to be an effective technique that reduces the likelihood of cache misses, thereby improving the overall performance of the system. Numerous prefetchers have been proposed to target sequential memory accesses [8, 39], strided access patterns [3, 24], irregular access patterns [6, 7, 23], and more complex designs that employ low-cost perceptron networks to predict diverse access patterns [5, 4]. A detailed overview of prefetchers can be found in [12, 34]. Among the most widely adopted prefetching techniques in systems are stride [3] prefetchers. Stride prefetchers can identify recurring patterns for accesses that are not necessarily separated with constant strides. These prefetchers are particularly effective for dense matrix operations and multi-dimensional array traversals [12]. Conventionally, stride prefetchers place prefetched blocks directly into the cache, which can lead to cache pollution by displacing useful datasets especially if the prefetcher is very aggressive. To that end, Joupi et al. [24] proposed placing prefetched blocks into a separate buffer, known as a stream buffer, and migrating the blocks to the cache only when requested by the core.

2.3 Predictable Prefetchers

While prefetchers significantly improve average system performance, their complexity makes them difficult to analyze, leading to overly pessimistic execution time bounds for requests. In this paper, we address two key factors contributing to this limitation:

-

Prefetchers can induce memory reordering, potentially leading to pathological scenarios where requests are delayed by prefetch requests fetching non-essential data. We address this limitation in Section 3.

-

A prefetcher can alter the state of cache lines by replacing existing blocks with prefetched blocks, or by modifying the ages of cache lines within a particular associative set. We address this limitation in Section 4.

Consequently, disabling hardware prefetchers is a common practice in real-time systems [14].

To mitigate the unpredictability inherent in prefetchers and capitalize on their performance gains, researchers in the real-time community have devised various software and hardware techniques. The work in [36, 29, 10] addresses this by introducing a software model that segments tasks into computational and memory phases, with data and code prefetched into the cache at the start of each memory phase. Other software-based approaches have investigated prefetching data into a scratchpad memory rather than the cache in a predictable manner [2, 41, 44, 40, 9]. Software-based approaches, while effective, often require modifying the code and potentially the compiler to incorporate prefetching instructions or directives.

Work proposing predictable prefetching through hardware modifications is scarcer. The most relevant solution is [13], whose authors propose a WCET-preserving hardware prefetcher for many-core systems. Their solution involves a memory-level prefetcher connected to a predictable interconnect with a fixed-priority scheme, which bounds the blocking periods for high and low-priority packets. However, as noted in [34], attaching a prefetcher at the memory side may not always be optimal, as the memory can only detect misses and lacks accurate knowledge of the core’s reference patterns and whether the prefetched blocks are hitting or missing in the cache. In their paper, they utilize idle system slots to issue prefetch requests and employ a variant of the stream buffer to temporarily store prefetched blocks. These blocks are only moved to the cache upon demand, helping to preserve the cache state and maintain its analyzability. However, as we demonstrate in Section 5, relying solely on idle slots for issuing prefetch requests can be suboptimal, especially when cores execute bandwidth-intensive workloads that leave few empty slots for prefetch requests.

3 DAMA: The proposed solution

In this section, we introduce DAMA, a dual arbitration mechanism that imposes a deterministic upper bound on the cumulative latency of latency-critical ) requests while optimizing the average-case processing of both and non-latency-critical () requests. We begin by describing the system model and underlying assumptions (Section 3.1). Following this, we outline the high-level architecture of the arbitration mechanism and explain the roles of its main modules (Section 3.2). We then provide a detailed description of how the entire regulation mechanism operates (Section 3.3). Finally, we present an illustrative example (Section 3.4) and formally discuss provided latency guarantees (Section 3.5).

3.1 System Model and Assumptions

We consider a system comprising distinct requestors , which may include cores, DMA engines, accelerators, bus masters, and more. We assume that a requestor can either issue requests, requests, or both, targeting a shared resource. For the sake of simplicity, we present our solution without considering data sharing between requestors. We denote to represent requests, originating from requestor and indexed by (e.g. ) according to their arrival time at the resource. We assume that a request is enqueued at the shared resource upon its arrival, and remains outstanding in the queue until it finishes being serviced; we denote the finishing time for request . We consider a discrete model of time, expressed in multiples of the clock period at the resource. We assume that it takes at least one clock cycle to service a request, hence , and that no more than one request can finish in any given clock cycle. We further assume that requests can be serviced in an out-of-order fashion and that a single requestor can have multiple outstanding requests.

Latency Model.

To precisely define the latency for , we lay out the following definitions, similar to previous work [31, 32, 33]:

Definition 1.

At clock cycle , the oldest request of (if any) is the earliest arrived request of that is still outstanding. We define as the time at which a request becomes oldest.

Given that in our model requests do not need to be serviced in the same order they arrive, a later arriving request can finish before an earlier arriving request. In this case, the later arriving request never becomes oldest. Note that if a request does become oldest, then is equal to either the time at which a previously arrived request finishes, or to , in case all previous requests of have already finished by that time. Since at most one request can finish in a clock cycle, two requests of cannot become oldest at the same time.

Definition 2.

We define as the queueing latency and as the processing latency of a request .

-

If is serviced before becoming the oldest request: then is equal to and to 0.

-

If becomes the oldest request before finishing being serviced: then is equal to and to .

Figure 1 depicts various scenarios for the processing and queueing latencies of 4 consecutive requests. In this example, we assume that initially, no request of is outstanding. This means that all previous requests issued by have finished, and thus becomes oldest as soon as it arrives. For that reason, the queueing latency for request is equal to zero. As outlined in Definition 2, and illustrated in Figure 1, our processing latency is the time the request spends in the queue after it becomes the oldest. Given that in our model requests do not need to be serviced in the same way they arrive, their processing time can be completely overlapped. Request exhibits this behavior by completing prior to , thereby incurring a processing latency of 0.

Task Delay.

As discussed in much related work [26, 19, 31, 32, 33], we argue that the delay suffered by a real-time task under analysis depends on the processing latency of its requests. Specifically, a core can stall while waiting for its cache’s demand requests to finish. If we consider demand requests from the core to be , then whenever the core issues multiple requests and stalls waiting for them to finish, the stall time is equal to the sum of their processing latencies. Therefore, we assume that the WCET of the task can be obtained by summing a base execution time (which might have to account for the effect of processor timing anomalies [16]) plus an upper bound to the cumulative processing time of requests. For this reason, in this paper we focus on bounding processing latency and not queueing latency 111Note that the queueing latency of a request is in any case upper bounded by the sum of processing latencies of oldest requests that are serviced while is outstanding.. A final concern is related to the ordering of requests issued by the core. To prevent requests issued by another task to be serviced before earlier requests by the task under analysis, we assume that a memory barrier is inserted whenever the task is preempted and upon its completion. In many architectures, such barrier is implemented by simply stalling the processor pipeline until all outstanding demand requests of the core have finished. This is equivalent to assuming that the barrier and subsequent instructions depend on previous demand requests of the task under analysis; hence, the effect of the barrier on the execution time of the task is similar to other data dependencies.

3.2 High Level Architecture

Queuing Structure.

Our arbitration scheme features two queues for each requestor: that handles requests, and that handles requests. This separation of queues ensures that the guarantees for requests are maintained, preventing requests from compromising them.

High Performance and Real-Time Arbiters.

DAMA comprises two arbiters: a high-performance arbiter (HPA) which is optimal for maximizing average performances and a real-time arbiter (RTA) which provides tight latency bounds. The HPA services both and requests flowing from the respective queues and , as illustrated in Figure 2. When operating in high-performance mode, both types of requests are given equal priorities, and the arbitration mechanism dictates the order in which they get serviced. For instance, if the HPA operates on a first-come first-served basis (FCFS), it services requests based on their arrival time. On the contrary, when operating in real-time mode, RTA only services requests originating from . The rationale behind blocking out requests in RTA is to provide a tight bound on the cumulative latency of requests while minimizing the time spent in this mode. Specifically, the RTA must provide a latency bounds of to oldest requests, in the sense that upon switching from HPA to RTA, regardless of the resource’s state, the oldest request of residing in must finish in at most clock cycles.

Latency Counters and Arbitration Mode Switcher.

As part of the system configuration, each requestor is assigned a value , which represents the target average per-request latency. In Section 3.5, we prove that the bound on the cumulative processing latency of requests is proportional to the total number of requests and . For each requestor, at run-time we maintain a counter that tracks the slack - that is, the difference between and the actual latency - accumulated by requests issued by requester . To prevent the latency counters from potentially growing more and more negative, we impose the constraint . The Arbitration Mode Switcher continuously monitors the value of the counters and forces the system to operate in RTA mode whenever the value of any counter is less than or equal to zero. At the start of the system (), each requestor’s latency counter is initialized to a maximum slack value as described in Algorithm 1 (lines 6-9). Intuitively, the higher the value of the initial slack and the higher the value of , the longer the system can remain in HPA mode, albeit at the cost of a larger latency bound for requests; we explore such tradeoff in Section 5.

3.3 Latency Regulation Mechanism

In this subsection, we describe the latency regulation mechanism outlined in Algorithm 1. After performing the system initialization at , the memory controller conducts a series of checks on a per-cycle basis. At every cycle, the queues are checked to determine whether outstanding requests are still waiting to be serviced (line 12). If this is the case, the counter of requestor is decremented by 1, indicating the passage of time and the consumption of 1 cycle from its latency budget (line 13). It is important to note that the latency counters are only updated when there are outstanding requests residing in and when these requests are serviced. This is because our mechanism focuses solely on regulating the latency of requests, with no consideration for regulating requests. Let be a function that returns a request that finishes at time . If such a request does not exist, the function returns NULL. At every cycle, the memory controller checks whether any of the oldest requests residing in queues have been serviced (line 15). If such a request exists, the latency counter for the corresponding requestor is incremented by the minimum between the maximum slack value , and the sum of the current counter value with (line 16). The purpose of this minimum operation is to bound the accumulated counter value, ensuring it does not exceed . This guarantees that the counter values will not grow indefinitely beyond which is essential to derive a latency bound for requests. After updating the value of the counters, we push the newly arrived requests into their respective queues and pop the ones that finished (line 18). At the end of each processing round, the status of the latency counters is checked. If any counter is less than or equal to zero (line 20), this indicates that requester has exhausted its allocated latency budget, and the arbiter executes in real-time mode (line 21). Transitioning to the RTA when any of the counters gets depleted is essential as this mode imposes a bound on the maximum service time of a request issued by requestor . Conversely, if all counters return to values above zero, the arbiter transitions back to high-performance mode (line 23). Note that both loops in Algorithm 3.3 depict how the hardware operates and are thus executed in parallel.

3.4 Illustrative Example

Figure 3 provides an illustrative example of how the counter value changes throughout the program’s execution, demonstrating how switches are performed accordingly. For this example, we assume , , and . The counter begins with a value initialized to , allowing the arbiter to operate in HPA mode, as the counter value is positive. At the first memory request from requestor 1 becomes the oldest. As it can be seen in the figure, the arrival time overlaps the time the request becomes oldest. This indicates that queue was empty and did not have any outstanding requests when arrived, which makes queuing time for equal to zero. After the request becomes oldest the counter starts decrementing by 1 with each cycle until the request gets serviced. At , request completes, prompting the controller to add to the counter. Although the counter would have reached 5 at , it is capped at to keep the value bounded. At and two new requests and become the oldest and the same behavior with the counters repeats. Notice that arrives at but does not become the oldest until since at is the oldest outstanding request that is still waiting to get serviced. At the counter reaches 0, prompting the controller to switch to RTA. In the worst-case scenario, the oldest request will spend at most cycles in RTA mode. The constraint ensures that when a request finishes, its counter will be greater than or equal to zero, as demonstrated at cycles 11 to 13. At cycle 13 since is serviced, the counter becomes greater than 0, and the arbiter switches back to HPA mode.

3.5 Latency Guarantees

We next formally prove the timing guarantee provided by DAMA. In what follows, let to denote the value of counter at clock cycle (after executing Algorithm 1 for that clock cycle). Also, let to denote the index of the first request of after that becomes oldest at some point. First, in Lemmas 3 and 4, we constraint the value of the counter whenever a request becomes oldest. Then, Theorem 5 uses the lemmas to compute a latency bound for a sequence of requests. Finally, Theorem 6 extends the bound to a task under analysis considering the effects of preemptions.

Lemma 3.

For all such that becomes oldest at some time .

Proof.

By induction on the index of requests of that become oldest.

Base case.

since there are no previous requests, the first request must become oldest when it arrives. By line 8 of Algorithm 1, is initialized to when the system starts, and furthermore, cannot be decremented until the clock cycle after the first request arrives (line 13). Hence: , and since we assume , the base case holds.

Induction case.

assuming that holds, we need to prove that also holds. Note that based on Algorithm 1, can only be incremented at line 16, where the current counter value is incremented by ; however, at the same line, the counter cannot be set to a value greater than . Hence, from , it immediately follows that it must also hold .

Next, consider the value of computed by the algorithm at time after subtracting 1 at line 13 (as itself is in the queue) but before increasing it at line 16. If such value is greater than or equal to 0, from it follows: . Otherwise, from and the fact that the counter is decremented by at most 1 in a cycle, there must exist a previous cycle such that and for all . Because arbitration switches to RTA when the counter reaches 0 and from the definition of , it follows that . Therefore, the value of at after line 13 cannot be smaller than , and since and , after line 16, it must be .

In summary, in any case it holds: . Finally, note that either arrives at or before , and then ; or , in which case no request of can be present in the queue at line 13 in , and thus the counter value is not modified. In either case, we obtain , concluding the proof.

Lemma 4.

For all such that becomes oldest at some time

| (1) |

where is the number of requests of (including ) that finish in .

Proof.

Based on line 16 of Algorithm 1 and definition of , counter is incremented by at most in . Furthermore, note that the number of clock cycles in the same interval when there is a request in the queue at line 13 is equal to ; hence, the counter is decremented by exactly . The lemma follows.

Theorem 5.

Let and assume that no request of with index greater than finish before requests with index less than or equal to . Then:

| (2) |

Proof.

Let and to be the first and last oldest request of such that . If neither exist, then no request with becomes oldest: therefore, and the theorem trivially holds. Otherwise, both must exist (note it may be ) and furthermore, .

Next note that since is oldest, by definition no request with can finish after . By assumption, no request with can finish before . Since becomes oldest either at , or when it arrives - in case there is no outstanding request of after - it follows that no request with can finish before either. Therefore, a request can complete in the interval only if , yielding:

| (3) |

Next, by summing Equation 1 over all oldest requests with and simplifying we obtain:

| (4) |

Using Lemma 3 to upper / under bound and and Equation 3 to upper bound , we obtain:

| (5) |

and since , the theorem holds.

Theorem 6.

Consider a job of a task under analysis performing requests and suffering context switches. Assume that every time the task is preempted and when it finishes executing, a barrier is inserted to prevent successive demand requests of the same core to be serviced before earlier requests of the task. Then the cumulative processing latency of the requests of the job is bounded by .

Proof.

Note that the number of context switches is equal to one (when the job starts) plus the number of times it is preempted. Since the task suffers context switches, it must issue requests with indexes in intervals , such that the sum of the requests in all intervals is equal to . Based on the barrier assumption, no request with index greater than can finish before a request with index in ; the same holds for the other intervals. Hence, we can apply Theorem 5 to each interval. Summing Equation 2 over the intervals yields a cumulative latency bound over all requests of the task:

| (6) |

Based on Theorem 6, when computing the WCET of a task, we suffer an overhead of for every context switch. Intuitively, this is because before the task starts and every time it is preempted, the slack counter for the core can be recharged to its maximum value. Such overhead can be reduced when performing schedulability analysis following the approach in [30]: instead of using the WCET of each job in a given busy interval, we first compute the cumulative base execution time and the cumulative number of requests over all jobs in the interval, i.e., we treat them as a single consecutive execution segment; then, we sum the obtained cumulative base execution time with the cumulative request latency bound to obtain an upper bound to the length of the interval. Since the analyzed segment executes without preemptions, the latency bound is equal to .

4 Predictable Prefetcher

In this section, we describe a predictable prefetcher that does not alter the state of cache lines, preserves the WCET analyzability of the cache, and maintains the cumulative processing latency of requests. As discussed in Section 3, we consider demand requests from the core to be ; while prefetch requests from the predictable prefetcher are .

4.1 Ensuring Predictability with a Prefetch Side Buffer

Conventionally, prefetchers place data fetched from main memory into the cache, thus altering the state of its cache lines. This alteration can involve replacing existing blocks with prefetched data or updating the ages of cache lines within a particular associative set. Incorporating this behavior into static WCET analysis is generally avoided due to its complexity. In our approach, we maintain WCET analyzability of the cache by using a prefetch side buffer, a concept first introduced in [24] and later adapted for real-time systems in [13]. This side buffer prevents cache pollution and avoids modifying the cache state by storing prefetched blocks separately and transferring them to the cache only upon a demand hit. However, it is important to note that although a prefetch side buffer prevents changes to the cache line state, it does impact the time needed to service a miss request. This is because, before introducing the prefetch side buffer, servicing a cache miss required accessing the main memory. However, with the side buffer, servicing a cache miss can either be handled by fetching the data from the main memory or by accessing the side buffer, which takes less time. Due to this difference in the time required to handle a cache miss, any static analysis tool used to determine the state of cache lines (e.g., always hit, always miss, etc.) must be able to account for these timing variabilities.

A core generates a demand request whenever it misses in the L1 data cache. Note that if finds a matching address for a block in the prefetch side buffer, it is not propagated to the memory controller; instead, the block is moved directly into the cache. Therefore, from the core’s perspective, the request’s processing latency is zero. By including the request in the sequence of requests issued by , we ensure that the total number of issued requests remains unchanged, with or without the prefetcher.

In Section 3.5, we provide a proof of how timing guarantees are ensured for requests when operating in RTA mode. Importantly, the introduction of the prefetch side buffer guarantees that, regardless of the prefetching strategy, prefetch requests do not interfere with the state of requests and therefore do not impact their timing. As a result, the previously derived bound on the cumulative latency of requests remains valid even with the addition of the prefetcher, and no modifications are required to account for it.

4.2 Features Integrated into our Predictable Prefetcher

When a prefetch request is issued by requestor , an request is created and added to its corresponding queue at the memory controller. Before servicing this request, the requestor may issue a demand request (considered to be ) to the same address. Under normal circumstances, this request would be inserted into its designated queue at its intended arrival time. However, this is problematic, as two requests targeting the same address would exist in and , both to be processed by the memory controller. To address this, we incorporate a request-merging mechanism. This mechanism involves retaining the request in and removing the request from . Before discarding the request, we merge any relevant information from it into the request, as required by the HPA. For instance, if the HPA operates on a FCFS basis, the merged information would be the arrival time of the request, which arrived before the request 222Note that from a hardware implementation perspective, FCFS is typically implemented through a queue of pointers to requests, ordered by arrival time. Hence, the merging operation effectively consists in overwriting the queue position previously occupied by the request with a pointer to the request.. This process ensures that the system behaves as though the earlier-arrived request was maintained, without affecting the cumulative processing latency bound of requests.

Another feature we incorporated into our system is incrementing the latency counter for requestor when it accesses a prefetched block that is already present in the prefetch side buffer. Conventionally, upon processing a demand request issued by requestor , the value would be added to its counter upon completion, as outlined in Algorithm 1. However, as discussed in Section 4.1, locating a matching block in the prefetch side buffer indicates that the request has already been prefetched, so there is no need to send a new request to the memory controller. This allows us to instantly increment the latency counter for the requestor that issued the demand request. Incrementing the counter in this way enables us to maintain HPA mode for a longer period, thereby avoiding a transition to RTA mode.

4.3 Handling Prefetch Requests at the Cache Controller Side

Implementing the predictable prefetcher described in the previous subsections requires modifying the cache controller to handle prefetched blocks differently. In our model, we assume a cache controller that includes a prefetch side buffer, implemented as a fully associative cache, along with two separate miss status holding register (MSHR) queues: one for demand requests and another for prefetch requests . An MSHR queue is used to track outstanding cache misses, storing information such as the address of the missed request. As discussed in [42], MSHRs can be a significant contention point and therefore require partitioning based on request criticality. In our model, we split the MSHR queues to prevent the prefetcher, which issues requests, from overwhelming the MSHR queue handling requests. This approach limits the number of prefetch requests that can be issued while ensuring that requestors issuing requests are never blocked by the prefetcher. Algorithm 2 outlines how the cache controller handles request packets sent from the core and the response packets received from the memory controller.

When a request arrives from the core, we first check if the requested data is available in the cache or the prefetch side buffer (line 8). If the data is not found and the request does not match a PFMSHR or DMSHR entry, a new entry is created in the appropriate MSHR queue (lines 9-14). Subsequently, the request is forwarded to the next level in the memory hierarchy (line 15). On the other hand, if a cache hit is encountered (line 18), the ages of the cache lines within the accessed set are adjusted (line 19). If a request packet from the core is received and is identified as being present in either the PFMSHR or the prefetch side buffer, there are two cases to consider:

-

Case 1: The received request packet corresponds to a demand request and matches the address of a prefetch request in the prefetch MSHR (line 20). This indicates that a demand request is accessing the same address as a prefetch request that has been issued but not yet serviced. As discussed in Section 4.2, in this case, the memory controller merges both requests by discarding the prefetch packet and transferring its information to the demand packet, which is then placed into the queue. To achieve this, the cache controller is modified to send a merge packet with all the required information, which the memory controller must receive and respond to accordingly (lines 21-24).

-

Case 2: The received request packet corresponds to a demand request that hits in the prefetch side buffer (line 25). This indicates that the demand request is accessing a block that was previously prefetched and stored in the prefetch side buffer. In this case, the block is copied to the cache and evicted from the prefetch side buffer. Additionally, as outlined in Section 4.2, when a demand request hits in the prefetch side buffer, the latency counter of the corresponding requestor is immediately incremented by . To facilitate this, we modify the cache controller to send a counter increment packet, which the memory controller must receive and handle accordingly (lines 26-32).

Note that in cases 1 and 2, sending merge and counter increment packets does not introduce additional interconnect overhead in our setup, as we assume a crossbar interconnect (see Section 5). This may not hold for other interconnect designs.

If a core tries to issue a demand request to an address already present in the , the corresponding instruction stalls until the response is received, and only then the demand request is processed by the cache. Similarly, if the prefetcher issues a request for a block that resides in the , the prefetch side buffer, or the cache, the prefetch packet is dropped.

Upon receiving a response packet from the memory controller, we first verify if it corresponds to a prefetch request (line 36). If so, this suggests that data for a prefetch request, which initially missed in the cache, has now arrived. We then check if there is space in the prefetch side buffer to accommodate this request (line 37). In the event that the buffer is full, the oldest prefetched block is evicted to make room for the incoming data (line 38-39). Once sufficient space is available, the new prefetched block is inserted into the prefetch side buffer, and the corresponding entry in the prefetch MSHR queue is subsequently freed (lines 41-44). However, if the response packet corresponds to a demand request, we allocate a new cache block, perform the necessary evictions, and insert the new block into the cache (lines 46-47). Note that if the evicted block is dirty, a writeback request is issued to the memory resource.

5 Evaluation

We implemented and evaluated our proposed solution, DAMA, using the gem5 simulation environment [28], operating in syscall emulation mode (code available at [1]). Our setup consists of eight 8-wide superscalar out-of-order RISC-V cores running at 2 GHz. Each core has a 4-way set-associative 32 KB instruction cache and a 4-way set-associative 16 KB write-back data cache, with the sizes chosen to align with the tested benchmarks’ working set sizes. All instruction and data caches are connected to a shared memory through a crossbar interconnect. A crossbar is considered since our work does not focus on handling interconnect contention. For this implementation, we employ the gem5’s simple memory model with a fixed latency of 30ns. Note that this model makes an arbitration decision every 30ns; therefore, from a model perspective, it is equivalent to a resource with a clock period of 30ns and a service time of clock cycle per request. The caches include 32-entry MSHR queues. In experiments using a predictable stride prefetcher attached to the L1 data cache, we maintain two separate MSHR queues: one with 8 entries for prefetch requests and another with 24 entries for demand requests. We selected the stride prefetcher [3] for our experiments; however, our proposed method is independent of the prefetcher type and can be applied to any. We adopt FCFS arbitration as the HPA, while as RTA we employ RR arbitration among the requestors, prioritizing the oldest request of each requestor. Note that both arbiters service requests of a given requestor in the order they arrive at the memory controller.

To evaluate our proposed solution, we conduct various experiments using combinations of the San Diego Vision (SDV) [43], PolyBench [37], and synthetic IsolBench [42] benchmark suites. In most experiments, we run IsolBench on the background cores to demonstrate how DAMA responds to adversarial cores attempting to saturate the shared memory resource. Specifically, we run the bandwidth-intensive Isolbench benchmark, which misses in the L1 cache for all requests and thus maximizes the number of requests sent to the memory controller. In one set of experiments, we use SDV as a real-world benchmark to demonstrate how DAMA ensures requests meet their cumulative and per-request bounds. In another set of experiments, we run the linear algebra kernels in Polybench to demonstrate DAMA’s effectiveness when paired with a stride prefetcher and compare it against the predictable prefetch-based arbitration policy proposed in [13]. Polybench was chosen for its stride-based memory access patterns, which frequently trigger our attached prefetcher.

In this section, we begin by demonstrating how DAMA achieves latency bounds. We then attach a predictable prefetcher, examine how the size of the prefetch side buffer impacts the core’s IPC, and discuss how DAMA manages prefetch requests. Our comparison is against a variation of the TDMA arbitration mechanism proposed in [13]. Because our focus is not on contention at the interconnect level, we chose to abstract away the predictable interconnect proposed in the original work. For this reason, we employ a similar arbitration scheme, with the slight variation being that our approach allocates a single memory slot per core in a round-robin fashion, while their interconnect setup allows for multiple slots per core. Due to the limitations of the simulation environment, which does not support attaching a prefetcher to the memory side, we attached multiple prefetchers to the L1 data caches of the cores. Finally, we compare against the Duetto scheme, both without and with the predictable prefetcher, extending the mechanism to incorporate requests. Our implementation follows the approach in [31], where the latency estimator runs in parallel with the HPA, and determines an upper bound to the remaining latency of the oldest request of each requestor based on the state of the RR arbiter and the queues. Similarly to DAMA, the RTA ignores requests.

5.1 Achieving Latency Bounds with DAMA

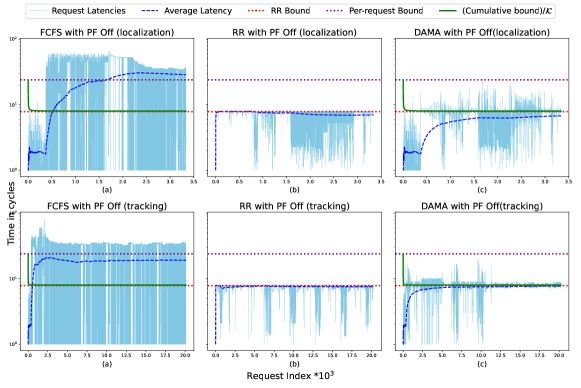

In this section, we experimentally demonstrate DAMA’s latency guarantees by running a subset of real-world SDV benchmarks on the foreground core and the synthetic bandwidth-intensive IsolBench benchmark on the background cores. Our goal is to show that, under DAMA, the foreground core meets its derived per-request and cumulative latency bounds even when background cores are acting in an adversarial manner. In this set of experiments, we regulate the latency of requests originating from the foreground and background cores. This means that if any counter for any gets depleted a switch to RTA is prompted. Figure 4 delineates the processing latency of requests for the foreground core executing SDV benchmarks under FCFS (HPA), RR (RTA), and DAMA. It also shows the per-request RR and DAMA bounds, the cumulative processing latency bound scaled by the number of requests , and the average latencies of requests. We scale the cumulative bound by and display the average latency instead of the total latency for clearer visualization. For all experiments, unless otherwise stated, we configure DAMA’s parameters as follows: , , . Under RR, the worst-case scenario occurs when a switch to RR happens after starting to process an request, causing the next request in RR order to suffer a waiting time of plus the maximum waiting time in RR which is . Hence, the RR per-request bound is computed as . Since in our case , our per-request RR bound becomes . Under DAMA, the worst-case processing latency of an request occurs when the counter starts at its maximum value when becomes oldest. Because our employed arbiters process requests of at the memory controller in order, no other request of can finish while is oldest. Therefore, in the worst case the counter keeps decrementing until it reaches 0 and the arbiter switches to RTA mode. Then, the requests takes an additional cycles to get serviced. Consequently, the maximum latency that could be experienced by a single request under DAMA in this experiment cannot exceed .

Figure 4 illustrates how requests executing under FCFS experience substantial latency spikes. This is because FCFS prioritizes requests based on their arrival time, and the high volume of background core requests overloads the shared memory resource. As a result, the requests issued by the foreground core face significant delays, leading to the average latency exceeding the scaled cumulative latency bound. Under RR, however, the maximum latency experienced by a foreground core request remains within the bound imposed by RR. Consequently, the average latency of requests saturates at this bound and never exceeds it. The DAMA model, on the other hand, keeps executing requests in FCFS mode until the counter is depleted, at which point it switches to RR mode. This explains the latency spikes that surpass the RR bound but stay within the per-request bound imposed by DAMA in both benchmarks and . It is important to note that the foreground core does not always trigger the switch to RTA mode. As a result, requests on the foreground core may not always experience latency spikes, since this depends on the core’s access pattern and the possibility of other cores triggering a switch. This helps explain why has fewer latency spikes than . As for the average latency of requests, we can see that it consistently remains below the scaled cumulative bound and eventually saturates at the RR bound. This saturation occurs because scaling the cumulative bound by results in the expression which corresponds to the cumulative bound with in Theorem 6. As the number of requests increases, the first term approaches zero, leaving only which is equal to the RR bound in this experiment.

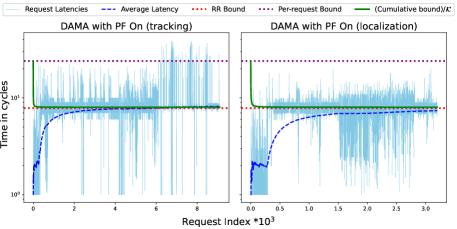

In Figure 5, we experimentally demonstrate that after enabling the prefetcher on all cores the cumulative processing latency bound is still honored for and benchmarks. However, the benchmark exhibits per-request latency spikes, suggesting that the previous per-request latency bound is violated upon enabling the prefetcher. This happens because, with the prefetcher enabled, DAMA allows requests to be serviced out of order in the specific case where a demand request hits the prefetch side buffer while the memory controller is still servicing an earlier demand request. In this scenario, the latency counter is incremented by , giving the request being serviced more time to continue executing in HPA mode, thereby exceeding the previous per-request latency bound. We remark that the focus of our approach is on bounding the cumulative processing latency of requests, allowing flexibility with the latency of individual requests to maintain the system in HPA mode as long as possible.

5.2 Impact of Prefetch Side Buffer Size on IPC

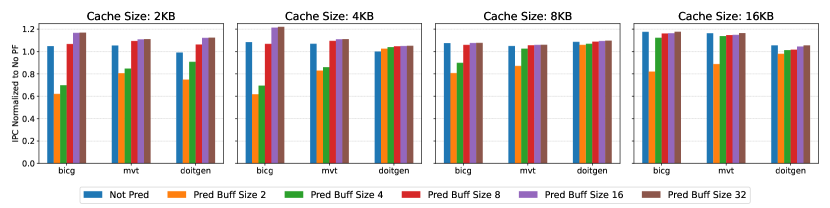

To evaluate the influence of prefetch buffer size on average performance, we executed a subset of linear algebra kernels from PolyBench on a single core. Figure 6 depicts the normalized Instructions Per Cycle (IPC) of the core for various cache and prefetch buffer sizes, relative to a configuration without a prefetcher. As observed, most benchmarks exhibit a performance increase with larger cache sizes. This is attributed to the larger cache’s ability to accommodate more prefetch blocks, potentially reducing cache evictions. For example, benchmarks and experienced an approximate 15% IPC boost when the cache size was increased from 2KB to 16KB.

As Figure 6 illustrates, for small cache sizes the prefetch side buffer can perform even better than a conventional (not pred) prefetcher. For example, with a 2KB cache, benchmarks , , and experienced IPC increases of 12%, 5%, and 21%, respectively, with a 16-entry buffer. This improvement occurs because the prefetch side buffer stores prefetched blocks until they are needed, reducing cache pollution, especially when the prefetcher is aggressive. However, if the buffer is too small, performance can degrade significantly. In this case, prefetched data may be evicted before it is needed, leading to wasted prefetch effort. This behavior is exhibited with a prefetch buffer size of 2 and 4 for all benchmarks. Based on these results, we chose an 8-entry prefetch buffer, as Figure 6 indicates this configuration achieves near-optimal performance with a 16KB cache. Additionally, the extra memory overhead for this configuration is minimal, amounting to 3%. Note that we evaluated multiple prefetcher types (IPC results are in the supplementary material at [1]), and we selected the Stride Prefetcher due to its superior performance across various PolyBench benchmarks.

5.3 Handling Prefetch Requests with DAMA

In this series of experiments, we evaluate the effectiveness of DAMA when we attach a predictable stride prefetcher to the L1 data caches of the system. To evaluate how DAMA performs when the prefetcher is enabled we use two different benchmark setups described as follows: (1): The foreground core executes PolyBench benchmarks, while all the background cores run bandwidth-intensive workloads. (2): We execute eight distinct PolyBench benchmarks, each assigned to a separate core.

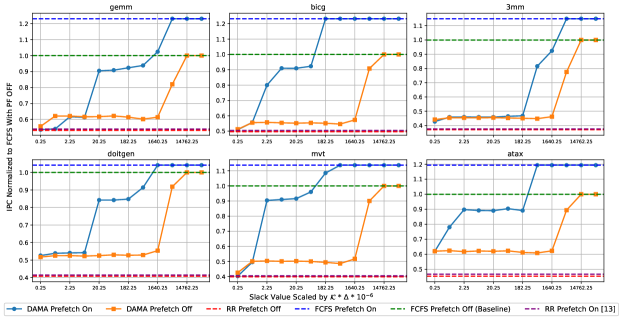

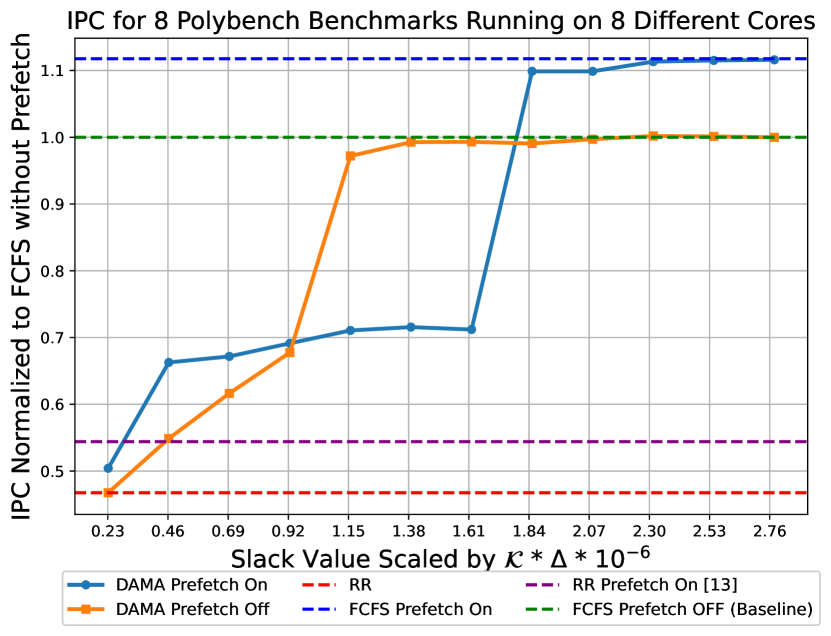

Figure 7 illustrates the normalized average IPC for DAMA across all cores with and without the prefetcher across various slack values, relative to the FCFS configuration without a prefetcher under setup 1.

Performance under FCFS and RR (setup 1).

When the prefetcher is disabled, Figure 7 shows that the RR scheme performs poorly compared to FCFS. While RR may benefit the core running PolyBench benchmarks by giving it a fair opportunity to send requests, it severely harms the performance of background cores running IsolBench, which are bandwidth-intensive. In contrast, FCFS prioritizes requests based on arrival time, resulting in a notable increase in average IPC. Figure 7 also illustrates that enabling the predictable prefetcher leads to a significant performance boost across all benchmarks under FCFS, with a maximum improvement of 22% compared to the configuration without a prefetcher.

Performance under DAMA while varying (setup 1 and setup 2).

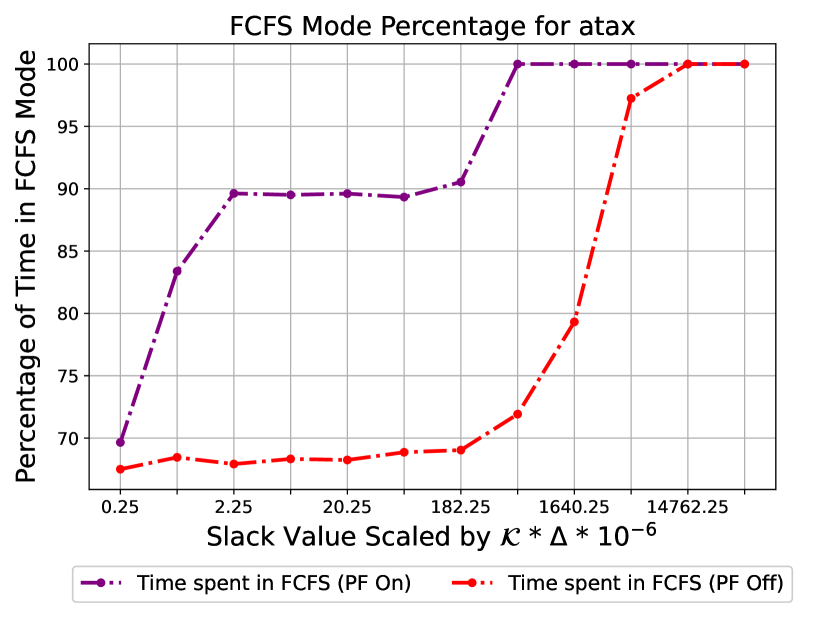

Figure 7 illustrates the impact of on the average IPC of the system under DAMA in setup 1. We scale the x-axis by to represent the additional latency overhead introduced by the slack relative to the total number of requests multiplied by . This provides insight into how increasing affects the cumulative latency bound. As increases, DAMA’s performance converges to FCFS performance, both with and without the prefetcher. This demonstrates that larger slack values enable DAMA to sustain HPA mode until one of the counters gets depleted. Notably, a minimal increase of in slack is sufficient for most benchmarks to achieve optimal FCFS performance with the prefetcher enabled, while a larger increase of is required when the prefetcher is disabled. DAMA with the prefetcher enabled converges to the optimal solution with a smaller value relative to the configuration where the prefetcher is disabled. This is attributed to the counter adjustment feature that we incorporated into our model, as detailed in Section 4.2. As a result, DAMA can remain in HPA mode for a longer duration even with a small slack value. Under the same setup, Figure 9 illustrates the percentage of time spent in FCFS as a function of for the benchmark. This plot exhibits the same trend as Figure 7 since a higher IPC is associated with more time spent in HPA mode by the arbiter compared to RTA mode.

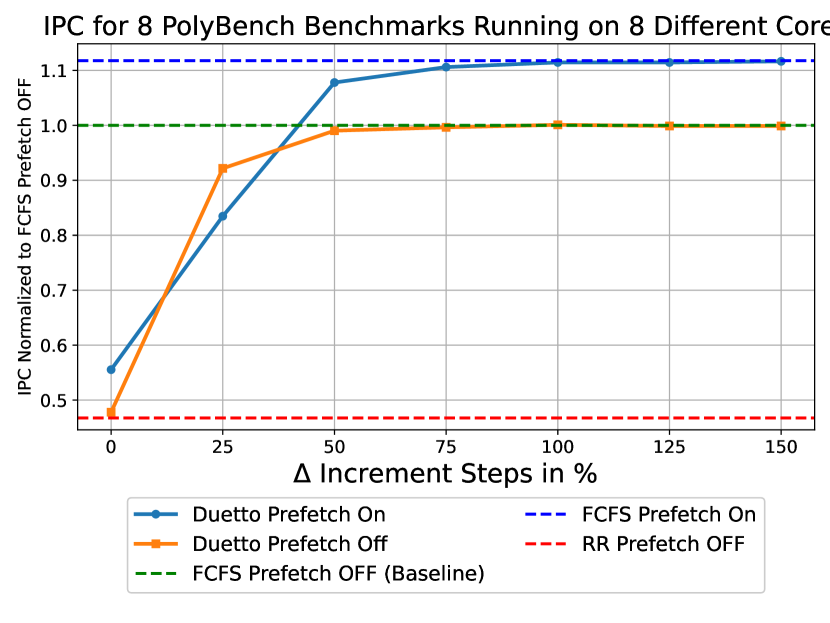

In setup 2, we run a distinct linear algebra benchmark on each core. Figure 9 illustrates the normalized IPC relative to the scaled . While the average IPC trend remains consistent with the previous setup, a notable observation emerges: DAMA converges to the optimal FCFS mode for both configurations (prefetcher on and off) with a remarkably small slack value of . This suggests that when cores execute real-world workloads that do not excessively overwhelm the shared memory resource, optimal performance can be achieved with minimal slack, resulting in negligible overhead.

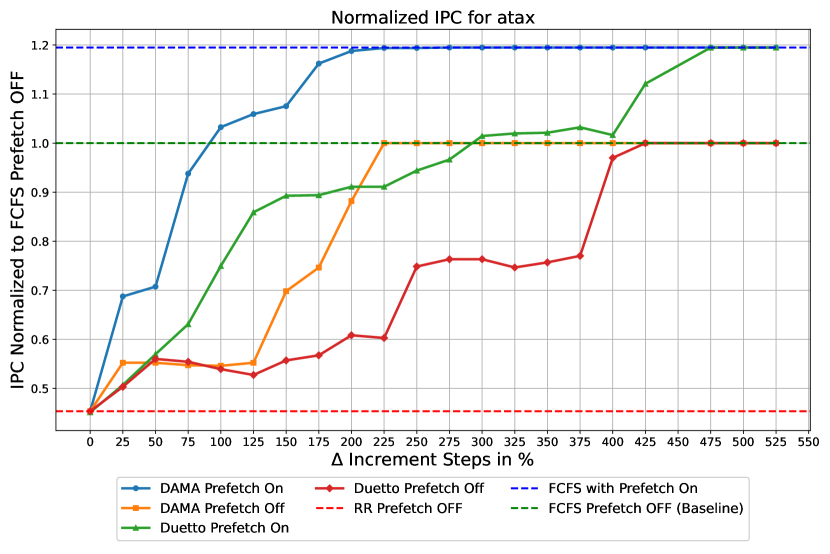

Performance under DAMA while varying (setup 1).

Figure 11 shows how varying affects the average IPC under DAMA for a setup running the atax benchmark on the foreground core and a bandwidth-intensive benchmark on the background cores. In this experiment, the slack value is fixed to , while increases incrementally by . The results indicate that a increment in allows DAMA to reach optimal performance for both prefetcher-enabled and prefetcher-disabled configurations. Since the cumulative latency bound is given by , increasing by 225% causes a proportional increase in the bound. On the other hand, the slack value () that achieves optimal performance results in an increase in the bound of only 1.5%. Hence, upon attempting to balance between tight bounds and performance, it is advisable to vary the slack value rather than . Note that we do not repeat this experiment for setup 2 since a very small slack value of is already sufficient to reach FCFS performance.

Comparison with [13] (setup 1 and setup 2).

We evaluate our approach against the arbitration scheme proposed in [13] using setup 1 and setup 2. In setup 1, our experiments indicate that our adaptation of the arbitration scheme proposed in [13] performs poorly in this setup, yielding results similar to the RR arbitration scheme as can be seen in Figure 7. This outcome arises because the background cores generate a high volume of requests to the shared resource, leaving no slots available for issuing prefetch requests. However, in setup 2, the scheme proposed in [13] demonstrated an 8% improvement over RR as can be seen in Figure 9. This advantage is due to the fact that, with real-world benchmarks, memory resources are not always fully saturated, allowing the arbitration scheme to find opportunities to issue prefetch requests.

In both setups, our approach shows a performance advantage over the work presented in [13], though it is important to note that our simulation environment differs from theirs, which imposes some limitations on direct comparisons.

Performance under Duetto[31] (setup 1 and setup 2).

Under Duetto, the only tunable parameter for achieving optimal performance is . Figure 11 illustrates that increasing by 475% enables Duetto to reach the optimal performance, while proportionally worsening the bound. This behavior is encountered in setup 1 where the background cores generate a high volume of memory requests. Figure 11 shows that in setup 2, a 75% increase in is sufficient for Duetto to achieve optimal performance. Note that in this Duetto implementation, small values did not yield significant performance improvements compared to [31]. This is because our memory model is not bankized and therefore does not exploit bank parallelism to improve performance.

5.4 Discussion

Comparison with the Duetto model.

Our evaluation shows that the flexibility added by the slack counter in DAMA is more effective in maintaining the system in HPA mode compared to the precise per-request latency estimation of Duetto: DAMA converges to FCFS performance with lower increase on the task cumulative latency bound compared to Duetto, which even in setup 2 requires a 75% increase with respect to the RR bound. From an analytical perspective, DAMA requires only a bound on the latency offered by the RTA to any request, while the latency estimator in Duetto must compute a dynamic bound based on the run-time state of the RTA arbiter, the memory resource, and the queues. For example, when applied to the more complex resource in [32], the latency estimator needs to consider up to 10 different cases, and perform a significant number of operations, which include a sequence of accessing lookup tables, 6 additions, and a comparison in the same clock cycle. However, in DAMA, independently of the specific memory resource, the only required hardware operations are comparison with zero and increment by a constant or decrement by one, performed in parallel on all counters. While a detailed hardware comparison would require an RTL implementation and is outside the scope of this paper, we thus find DAMA simpler to implement than Duetto.

Limitations.

similar to Duetto, DAMA requires modifications at the resource arbiter. While simple resources do not require changes to the HPA, for complex resources, as discussed in [32], the state of the HPA might need to be reset upon switching to the RTA. Similarly, the bound must account for requests that are being processed by the resource when the switch to RTA happens.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we introduced DAMA, a dual arbitration mechanism that provides an upper bound on the cumulative processing latency of requests without unduly impacting the performance of requests. Our model employs an efficient monitoring mechanism that informs the memory controller when a switch in arbitration mode is needed. We attach a predictable prefetcher to our L1 data caches as a source of requests and leverage the properties of this mechanism to further enhance the average performance of the system without impacting the bounds. Our experiments demonstrate that, with a minimal overhead of 1.5% on the cumulative latency bound, DAMA without a prefetcher achieves up to a 60% improvement in IPC over RR. Furthermore, we demonstrated that DAMA can fully leverage the potential of a prefetcher, achieving an average performance increase of 22% compared to the configuration with the prefetcher disabled.

Our future work includes implementing a mechanism that drops stale prefetch requests from the prefetch MSHR when the system remains in real-time mode for an extended period of time. Additionally, we plan to investigate combining our latency regulation mechanism with a complementary bandwidth regulation mechanism, since the number of requests issued by each core can significantly affect both performance and fairness of the system.

References

- [1] https://github.com/wlawand99/gem5/tree/pred-prefetcher.

- [2] Oren Avissar, Rajeev Barua, and Dave Stewart. An optimal memory allocation scheme for scratch-pad-based embedded systems. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems (TECS), 1(1):6–26, 2002. doi:10.1145/581888.581891.

- [3] Jean-Loup Baer and Tien-Fu Chen. An effective on-chip preloading scheme to reduce data access penalty. In Proceedings of the 1991 ACM/IEEE conference on Supercomputing, pages 176–186, 1991. doi:10.1145/125826.125932.

- [4] Rahul Bera, Konstantinos Kanellopoulos, Shankar Balachandran, David Novo, Ataberk Olgun, Mohammad Sadrosadat, and Onur Mutlu. Hermes: Accelerating long-latency load requests via perceptron-based off-chip load prediction. In 2022 55th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), pages 1–18. IEEE, 2022. doi:10.1109/MICRO56248.2022.00015.

- [5] Rahul Bera, Konstantinos Kanellopoulos, Anant Nori, Taha Shahroodi, Sreenivas Subramoney, and Onur Mutlu. Pythia: A customizable hardware prefetching framework using online reinforcement learning. In MICRO-54: 54th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, pages 1121–1137, 2021. doi:10.1145/3466752.3480114.

- [6] Mark Jay Charney. Correlation-based hardware prefetching. Cornell University, 1995.

- [7] Trishul M Chilimbi and Martin Hirzel. Dynamic hot data stream prefetching for general-purpose programs. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN 2002 Conference on Programming language design and implementation, pages 199–209, 2002. doi:10.1145/512529.512554.

- [8] Fredrik Dahlgren, Michel Dubois, and Per Stenstrom. Sequential hardware prefetching in shared-memory multiprocessors. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, 6(7):733–746, 1995. doi:10.1109/71.395402.

- [9] Minas Dasygenis, Erik Brockmeyer, Bart Durinck, Francky Catthoor, Dimitrios Soudris, and Adonios Thanailakis. A combined dma and application-specific prefetching approach for tackling the memory latency bottleneck. IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems, 14(3):279–291, 2006. doi:10.1109/TVLSI.2006.871759.

- [10] Guy Durrieu, Madeleine Faugère, Sylvain Girbal, Daniel Gracia Pérez, Claire Pagetti, and Wolfgang Puffitsch. Predictable flight management system implementation on a multicore processor. In Embedded Real Time Software (ERTS’14), 2014.

- [11] Leonardo Ecco, Sebastian Tobuschat, Selma Saidi, and Rolf Ernst. A mixed critical memory controller using bank privatization and fixed priority scheduling. In 2014 IEEE 20th International Conference on Embedded and Real-Time Computing Systems and Applications, pages 1–10. IEEE, 2014. doi:10.1109/RTCSA.2014.6910550.

- [12] Babak Falsafi and Thomas F Wenisch. A primer on hardware prefetching. Springer Nature, 2022.

- [13] Jamie Garside and Neil C Audsley. Wcet preserving hardware prefetch for many-core real-time sysatems. In Proceedings of the 22Nd International Conference on Real-Time Networks and Systems, pages 193–202, 2014.

- [14] Giovani Gracioli, Ahmed Alhammad, Renato Mancuso, Antônio Augusto Fröhlich, and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. A survey on cache management mechanisms for real-time embedded systems. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 48(2):1–36, 2015. doi:10.1145/2830555.

- [15] Danlu Guo and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. A requests bundling dram controller for mixed-criticality systems. In 2017 IEEE Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium (RTAS), pages 247–258. IEEE, 2017. doi:10.1109/RTAS.2017.12.

- [16] Sebastian Hahn, Michael Jacobs, and Jan Reineke. Enabling compositionality for multicore timing analysis. In Proceedings of the 24th international conference on real-time networks and systems, pages 299–308, 2016. doi:10.1145/2997465.2997471.

- [17] Mohamed Hassan, Hiren Patel, and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. A framework for scheduling dram memory accesses for multi-core mixed-time critical systems. In 21st IEEE Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium, pages 307–316. IEEE, 2015. doi:10.1109/RTAS.2015.7108454.

- [18] Mohamed Hassan, Hiren Patel, and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. Pmc: A requirement-aware dram controller for multicore mixed criticality systems. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems (TECS), 16(4):1–28, 2017. doi:10.1145/3019611.

- [19] Mohamed Hassan and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. Analysis of memory-contention in heterogeneous cots mpsocs. In 32nd Euromicro Conference on Real-Time Systems (ECRTS 2020). Schloss-Dagstuhl-Leibniz Zentrum für Informatik, 2020.

- [20] Farouk Hebbache, Mathieu Jan, Florian Brandner, and Laurent Pautet. Shedding the shackles of time-division multiplexing. In 2018 IEEE Real-Time Systems Symposium (RTSS), pages 456–468. IEEE, 2018. doi:10.1109/RTSS.2018.00059.

- [21] Bruce Jacob, David Wang, and Spencer Ng. Memory systems: cache, DRAM, disk. Morgan Kaufmann, 2010.

- [22] Javier Jalle, Eduardo Quinones, Jaume Abella, Luca Fossati, Marco Zulianello, and Francisco J Cazorla. A dual-criticality memory controller (dcmc): Proposal and evaluation of a space case study. In 2014 IEEE Real-Time Systems Symposium, pages 207–217. IEEE, 2014. doi:10.1109/RTSS.2014.23.

- [23] Doug Joseph and Dirk Grunwald. Prefetching using markov predictors. In Proceedings of the 24th annual international symposium on Computer architecture, pages 252–263, 1997. doi:10.1145/264107.264207.

- [24] Norman P Jouppi. Improving direct-mapped cache performance by the addition of a small fully-associative cache and prefetch buffers. ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News, 18(2SI):364–373, 1990. doi:10.1145/325164.325162.

- [25] Manolis Katevenis, Stefanos Sidiropoulos, and Costas Courcoubetis. Weighted round-robin cell multiplexing in a general-purpose atm switch chip. IEEE Journal on selected Areas in Communications, 9(8):1265–1279, 1991. doi:10.1109/49.105173.

- [26] Hyoseung Kim, Dionisio De Niz, Björn Andersson, Mark Klein, Onur Mutlu, and Ragunathan Rajkumar. Bounding memory interference delay in cots-based multi-core systems. In 2014 IEEE 19th Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium (RTAS), pages 145–154. IEEE, 2014. doi:10.1109/RTAS.2014.6925998.

- [27] Namhoon Kim, Bryan C Ward, Micaiah Chisholm, James H Anderson, and F Donelson Smith. Attacking the one-out-of-m multicore problem by combining hardware management with mixed-criticality provisioning. Real-Time Systems, 53:709–759, 2017. doi:10.1007/S11241-017-9272-9.

- [28] Jason Lowe-Power, Abdul Mutaal Ahmad, Ayaz Akram, Mohammad Alian, Rico Amslinger, Matteo Andreozzi, Adrià Armejach, Nils Asmussen, Brad Beckmann, Srikant Bharadwaj, et al. The gem5 simulator: Version 20.0+. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.03152, 2020.

- [29] Renato Mancuso, Roman Dudko, and Marco Caccamo. Light-prem: Automated software refactoring for predictable execution on cots embedded systems. In 2014 IEEE 20th International Conference on Embedded and Real-Time Computing Systems and Applications, pages 1–10. IEEE, 2014. doi:10.1109/RTCSA.2014.6910515.

- [30] Renato Mancuso, Rodolfo Pellizzoni, Marco Caccamo, Lui Sha, and Heechul Yun. Wcet(m) estimation in multi-core systems using single core equivalence. In 2015 27th Euromicro Conference on Real-Time Systems, pages 174–183, 2015. doi:10.1109/ECRTS.2015.23.

- [31] Reza Mirosanlou, Mohamed Hassan, and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. Duetto: Latency guarantees at minimal performance cost. In 2021 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), pages 1136–1141. IEEE, 2021. doi:10.23919/DATE51398.2021.9474062.

- [32] Reza Mirosanlou, Mohamed Hassan, and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. Duomc: Tight dram latency bounds with shared banks and near-cots performance. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Memory Systems, pages 1–16, 2021. doi:10.1145/3488423.3519322.

- [33] Reza Mirosanlou, Mohamed Hassan, and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. Parallelism-aware high-performance cache coherence with tight latency bounds. In 34th Euromicro Conference on Real-Time Systems (ECRTS 2022). Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, 2022.

- [34] Sparsh Mittal. A survey of recent prefetching techniques for processor caches. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 49(2):1–35, 2016. doi:10.1145/2907071.

- [35] Onur Mutlu and Thomas Moscibroda. Parallelism-aware batch scheduling: Enhancing both performance and fairness of shared dram systems. ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News, 36(3):63–74, 2008. doi:10.1109/ISCA.2008.7.

- [36] Rodolfo Pellizzoni, Emiliano Betti, Stanley Bak, Gang Yao, John Criswell, Marco Caccamo, and Russell Kegley. A predictable execution model for cots-based embedded systems. In 2011 17th IEEE Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium, pages 269–279. IEEE, 2011. doi:10.1109/RTAS.2011.33.

- [37] Louis-Noël Pouchet and Tomofumi Yuki. Polybench/c, 2016. URL: http://polybench.sourceforge.net.

- [38] Scott Rixner, William J Dally, Ujval J Kapasi, Peter Mattson, and John D Owens. Memory access scheduling. ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News, 28(2):128–138, 2000. doi:10.1109/ISCA.2000.854384.

- [39] Alan Jay Smith. Sequential program prefetching in memory hierarchies. Computer, 11(12):7–21, 1978. doi:10.1109/C-M.1978.218016.

- [40] Muhammad Refaat Soliman and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. Wcet-driven dynamic data scratchpad management with compiler-directed prefetching. In 29th Euromicro Conference on Real-Time Systems (ECRTS 2017). Schloss-Dagstuhl-Leibniz Zentrum für Informatik, 2017.

- [41] Vivy Suhendra, Tulika Mitra, Abhik Roychoudhury, and Ting Chen. Wcet centric data allocation to scratchpad memory. In 26th IEEE International Real-Time Systems Symposium (RTSS’05), pages 10–pp. IEEE, 2005.

- [42] Prathap Kumar Valsan, Heechul Yun, and Farzad Farshchi. Taming non-blocking caches to improve isolation in multicore real-time systems. In 2016 IEEE Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium (RTAS), pages 1–12. IEEE, 2016.

- [43] Sravanthi Kota Venkata, Ikkjin Ahn, Donghwan Jeon, Anshuman Gupta, Christopher Louie, Saturnino Garcia, Serge Belongie, and Michael Bedford Taylor. Sd-vbs: The san diego vision benchmark suite. In 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Workload Characterization (IISWC), pages 55–64. IEEE, 2009. doi:10.1109/IISWC.2009.5306794.

- [44] Hui Wu, Jingling Xue, and Sri Parameswaran. Optimal wcet-aware code selection for scratchpad memory. In Proceedings of the tenth ACM international conference on Embedded software, pages 59–68, 2010.

- [45] Heechul Yun, Renato Mancuso, Zheng-Pei Wu, and Rodolfo Pellizzoni. Palloc: Dram bank-aware memory allocator for performance isolation on multicore platforms. In 2014 IEEE 19th Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium (RTAS), pages 155–166. IEEE, 2014. doi:10.1109/RTAS.2014.6925999.

- [46] Heechul Yun, Gang Yao, Rodolfo Pellizzoni, Marco Caccamo, and Lui Sha. Memguard: Memory bandwidth reservation system for efficient performance isolation in multi-core platforms. In 2013 IEEE 19th Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium (RTAS), pages 55–64. IEEE, 2013. doi:10.1109/RTAS.2013.6531079.

- [47] Alexander Zuepke, Andrea Bastoni, Weifan Chen, Marco Caccamo, and Renato Mancuso. Mempol: policing core memory bandwidth from outside of the cores. In 2023 IEEE 29th Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium (RTAS), pages 235–248. IEEE, 2023. doi:10.1109/RTAS58335.2023.00026.