COP Layer Encapsulating Non-Functional Requirements for Physical Systems on Hakoniwa Environment

Abstract

This paper contributes to solving two issues: (1) clearly defining Non-Functional Requirements (NFRs) and Functional Requirements (FRs), and (2) simulating on a practical IoT platform. Related to the first problem, we always feel annoyed with many irregular conditions and non-requirements for programming physical systems. Particularly, they sometimes cause cross-cutting concerns problems. Thus, we cannot concentrate on mainstream behavior. Regarding the second problem, the platform must deal with IoT problems. Modern physical systems are integrated with the Internet of Things (IoT), which connects multiple devices, sensors, and cloud services. As a result, these systems may face problems such as latency, race conditions, deadlocks, and more. To solve these problems, we propose a robot software development environment called CPy4NFR. For the first problem, we draw NFRs in feature models, and CPy4NFR generates layers of Context-Oriented Programming (COP). The programming language is called CPy, which is an extension of Python. Through this process, the relation between non-functional requirements and COP is clarified, and the cross-cutting concern problems are solved. Regarding the second problem, CPy programs with NFRs are executed on Hakoniwa. Hakoniwa deals with IoT problems, provides APIs for simulator environments such as Unity and Unreal Engine, and supports APIs for physical robot systems. In this paper, we apply CPy4NFR to develop a drone system with changing behavior at runtime. Finally, we discuss two problems and the proposed development environment.

Keywords and phrases:

Context-Oriented Programming, Non-Functional Requirement, Real-Time SystemCopyright and License:

2012 ACM Subject Classification:

Software and its engineering Development frameworks and environments ; Software and its engineering Object oriented languages ; Software and its engineering Embedded softwareEditors:

Jonathan Edwards, Roly Perera, and Tomas PetricekSeries and Publisher:

Open Access Series in Informatics, Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik

Open Access Series in Informatics, Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik

1 Introduction

Engaging in programming can be enjoyable when we focus on mainstream behavior and have the ability to execute programs in real-time, such as with Live Programming. However, in practical development for physical systems like robots and vehicles, we often feel frustrated by the numerous requirements that fall outside of mainstream behavior. This frustration arises because these physical systems are influenced by their surrounding environments and must adhere to various regulations. These additional requirements are known as non-functional requirements (NFRs), which can include factors such as obstacles, living organisms, weather conditions, terrain, and legal constraints. Such physical systems are costly to construct. Thus, simulators play a crucial role in their development, as they help us to find potential issues before applying their software to physical systems.

However, reenacting non-functional requirements in a simulator can be challenging. Furthermore, modern physical systems are increasingly integrated with the Internet of Things (IoT), which connects multiple devices, sensors, and cloud services. As a result, these systems may face issues such as latency, race conditions, deadlocks, and more.

Therefore, this paper addresses the following issues.

-

(1)

Clearly define Non-Functional Requirements (NFRs) and Functional Requirements (FRs)

One of the main challenges with NFRs is that many of them are cross-cutting concerns. As mentioned earlier, physical systems encompass various types of NFRs. Therefore, it is essential to organize both NFRs and FRs using a structured model and to encapsulate the NFRs effectively. -

(2)

Simulate on a practical IoT platform

We need to construct a simulator on a platform that reenacts the IoT problems mentioned above and supports real robot behavior data. In this simulator, the program with encapsulated NFRs is executed.

To solve these issues, we propose a robot software development environment called CPy4NFR.

For the first problem, we draw NFRs in feature models [4, 5], and CPy4NFR generates layers of Context-Oriented Programming (COP)[3, 10]. The programming language is called CPy [8, 9]. Through this process, the relation between non-functional requirements and COP is clarified, and the cross-cutting concern problems are solved. Regarding the second problem, CPy programs with NFRs are executed on Hakoniwa [2]. Hakoniwa deals with IoT problems, provides APIs for simulator environments such as Unity and Unreal Engine, and supports APIs for physical robot systems.

In related works, Pierre Martou et al. proposed a combination of feature modeling and COP [6, 7]. The essential ideas of these studies are the same as our solution to the first problem. The difference is to practically deal with non-functional requirements because of the execution of Hakoniwa. Levent Yilmaz proposed a simulator based on the feature model [13]. However, this study has not applied to COP and not dealt with cross-cutting concerns. Therefore, the feature of CPy4NFR is its ability to address cross-cutting NFRs and simulate them in a practical virtual environment.

The remainder of this paper is as follows. Chapters 2, 3, and 4 briefly explain Hakoniwa, Feature Model, Case Study, and CPy. In Chapter 5, we propose CPy4NFR. Finally, Chapter 6 discusses CPy4NFR and concludes this paper.

2 Hakoniwa

Hakoniwa is an IoT platform on virtual environments and aims to simulate or educate to create IoT services. The team for Hakoniwa belongs to the TOPPERS project [11]. That has developed TOPPERS kernels, which are widely used in the automotive and embedded systems industry.

The motivation behind Hakoniwa is to provide real development experiences. Recently, IoT services have been organized through multiple systems, various devices, and cloud services, all connected via networks. For example, consider a smartphone remote controller used to operate a toy robot. The controller program is written in JavaScript, while the robot program uses C++. Both programs connect over Wi-Fi. For beginner programmers, this system may appear easy to develop. However, the smartphone controller may not work effectively with the robot due to wireless delays and other issues.

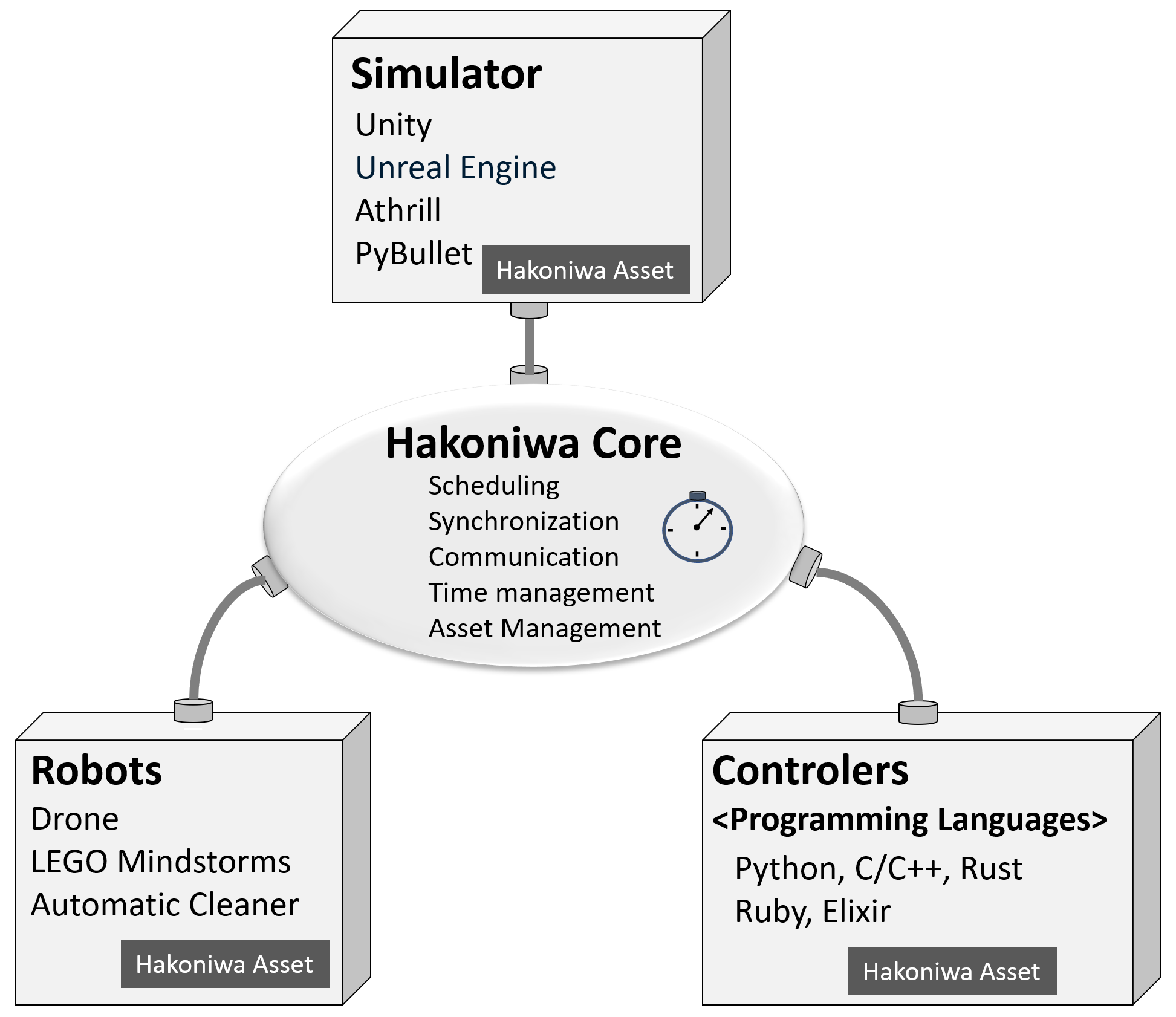

As shown in Figure 1, Hakoniwa comprises three elements: Hakoniwa-Core, Hakoniwa-Conductor, and Hakoniwa-Assets. This paper will not discuss the Hakoniwa-Conductor. The Hakoniwa-Core is responsible for managing the Hakoniwa-Assets, which include robots, simulators, and controllers. The robot assets represent the physical robots and provide the mechanisms for their behavior. Hakoniwa supports various types of robots, including drones, LEGO Mindstorms, and automatic cleaners.

The simulator-assets aim to move the robot, which is built by the robot assets, in a virtual environment. Hakoniwa supports Unity, Unreal Engine, and so on. We can construct realistic virtual environments like game development because of the simulator assets. Lastly, the controller assets facilitate programming using various programming languages, including Python, C/C++, Rust, Ruby, and Elixir.

Through this mechanism, we can develop a robot by using regular development tools and running it in realistic virtual environments. Additionally, Hakoniwa helps us to identify development issues similar to those encountered with the smartphone controller. In this paper, we apply Unity of simulator-assets and Python of controller-assets to move a drone of robots-assets.

3 Feature Model and Case Study

3.1 Feature Model

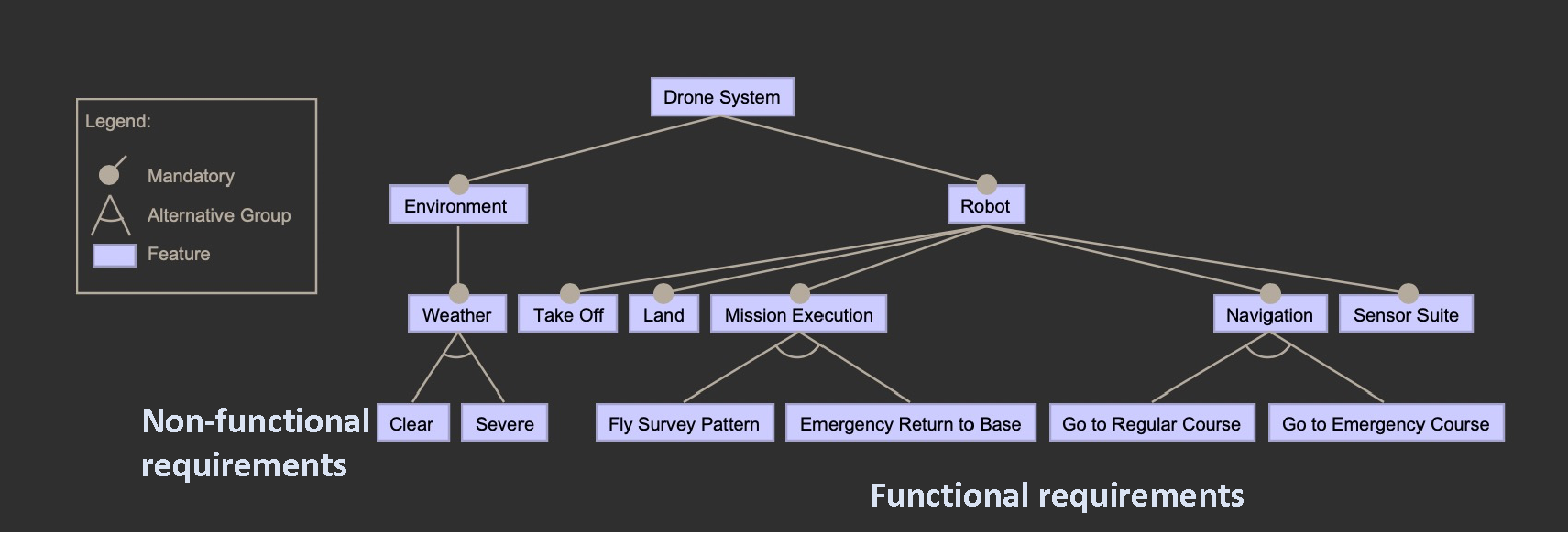

Feature Models aim to model functional and non-functional requirements (NFRs) as features. Figure 2 shows an example of a feature model for a drone system, which applies to the case study. This figure is drawn in FeatureIDE [1].

Each rectangle represents a feature. The notations for the relation between features are shown on the left side of the figure. The Drone system consists of a Drone and an Environment feature. Environment feature is an NFR. The Weather is an Optional Feature of the Environment Feature. The Weather feature is Clear or Severe. In this figure, non-functional requirements and functional requirements are shown inside each rounded rectangle. Additionally, “Clear” and “Severe” features are cross-cutting concerns between “Mission Execution” and “Navigation.”

3.2 Case Study

We consider a survey drone system whose behavior changes depending on the weather. In the “Clear” weather, the drone will go to regular course ( “Go to Regular course” ) and execute several surveys ( “Fly Survey Pattern” ). In the “Severe” weather, the drone will go to emergency course ( “Go to Emergency course” ) and cancel the mission and head back home ( “Emergency Return to Base” ). In other words, the robot contains two features related to mission ( “Mission Execution” ) and navigation ( “Navigation” ). “Mission Execution” consists of “Fly Survey Pattern” and “Emergency Return to Base.” “Navigation” consists of “Go to Regular Course” and “Go to Emergency Course” The keys are that “Clear” and “Severe”, which are non-functional requirements, affect both “Mission Execution” and “Navigation” which are functional requirements.

4 CPy

To deal with cross-cutting NFRs, we adopt Context-Oriented Programming called CPy.

CPy is an extension of Python for COP.

CPy has been developed and opened by Kenji Hisazumi et al. [8, 9]. Listing 1 shows an example of COP program using CPy. The base_route is declared as a base method using @cpybase. The sunny_route and the rainy_route are layer methods. Developers add layers to the base method using @base_method_name.layer_name decorator. The rainy_route includes proceed. The proceed calls the previously activated layer after the latest activated layer is executed. In the example, the sunny_route is executed after the rainy_route is executed.

5 CPy4NFR

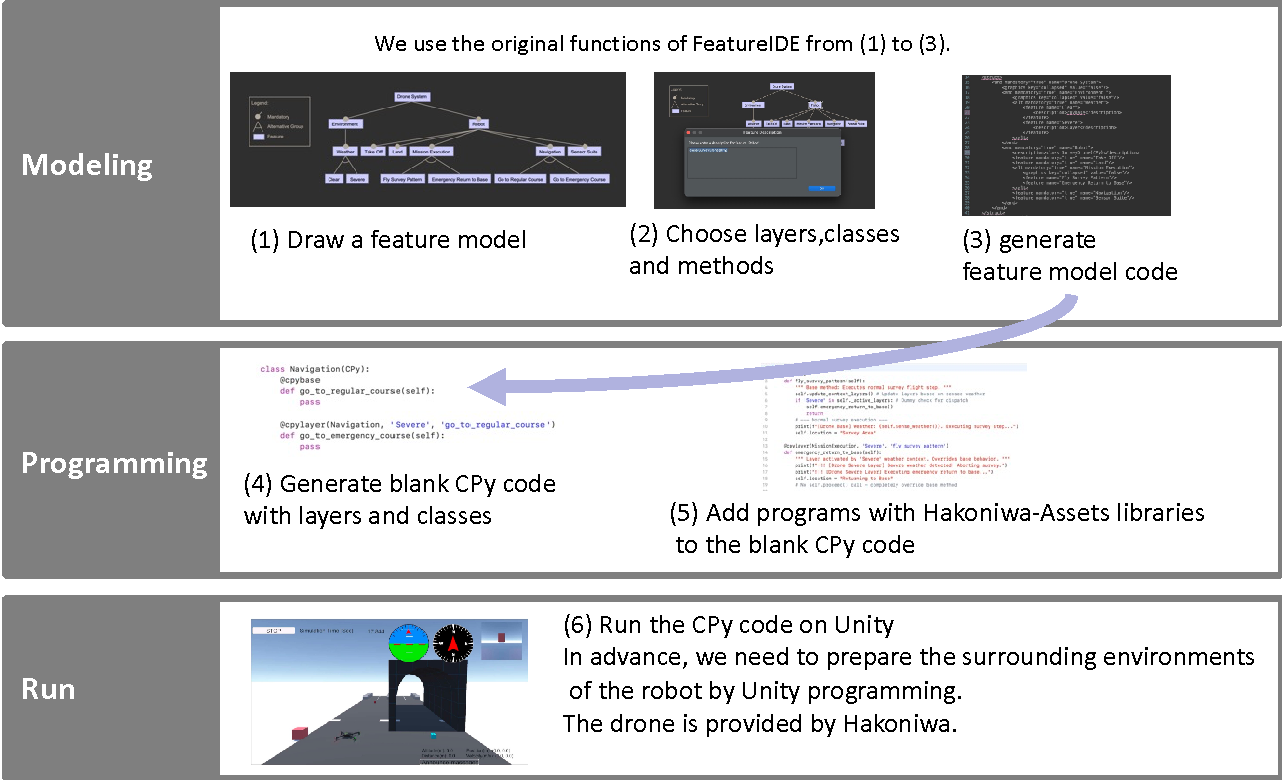

This chapter proposes a robot software development environment called CPy4NFR. Figure 3 shows the process of CPy4NFR. The following sections explain each step of the process. To explain the process, this chapter uses the case study in Chapter 3.

5.1 Modeling

In the modeling process, (1) we draw a feature model, (2) choose layers, classes and methods and (3) generate feature model code. The feature model was already shown in Figure 2. The following explains the step (2) and step (3).

5.1.1 How to choose layers, classes and methods

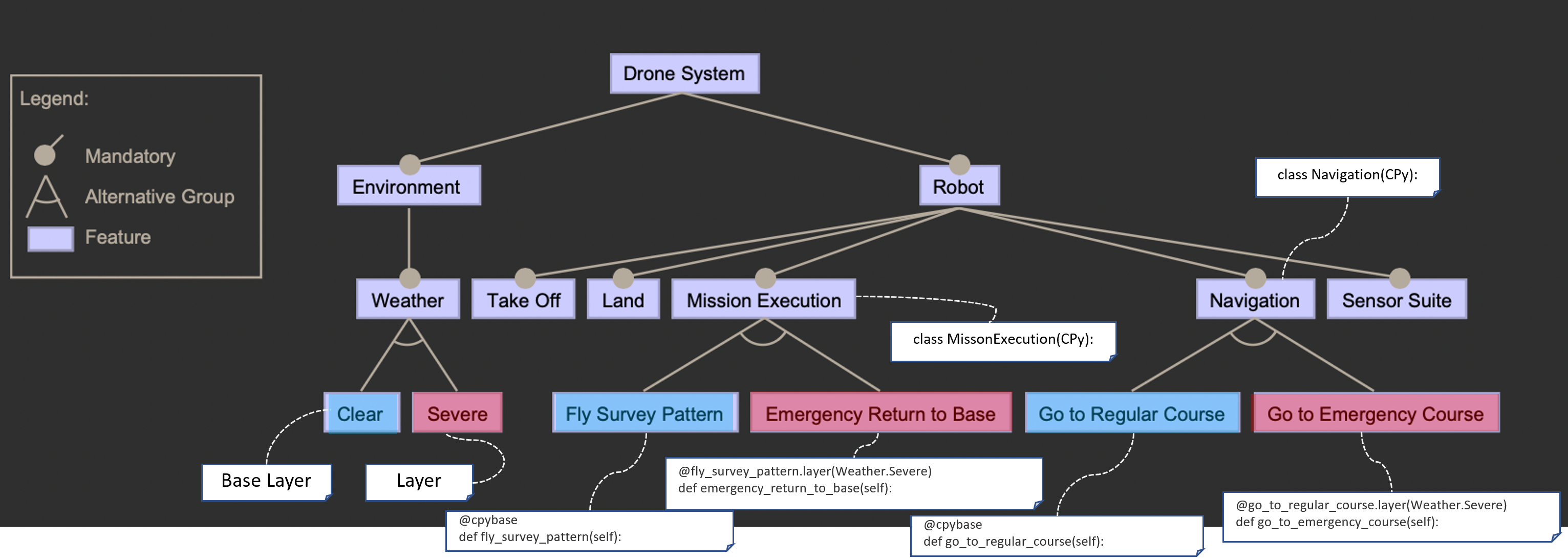

Figure 4 shows a feature diagram with descriptions for layers, classes, and methods, and Table 1 provides their descriptions. They are explained below.

-

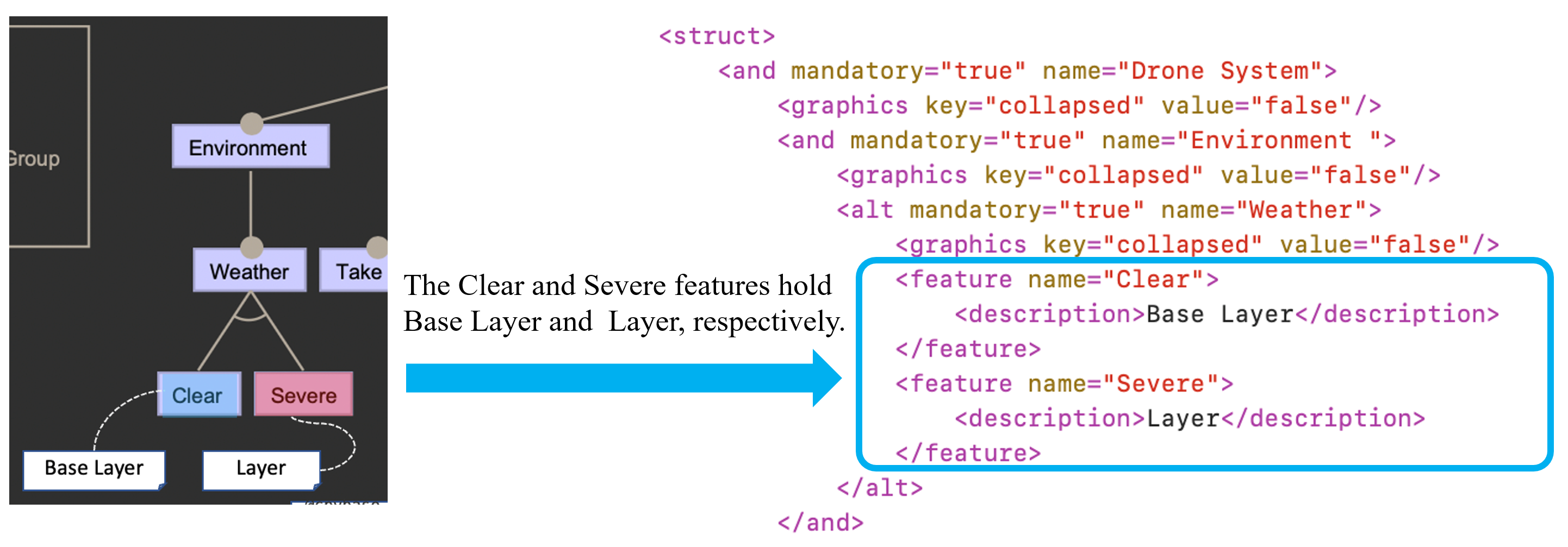

Layer

First, we select layers that include the base layer within the subtree related to non-functional requirements. In this case study, we have chosen the features within the subtree of “Environment,” which is a category of non-functional requirements, as candidates for this layer. We will designate “Clear” as the base layer and “Severe” as the normal layer. To clarify their roles, we will description them as “Base Layer” and “Layer,” respectively. -

Class

We select classes in features related to functional requirements. In this case study, we have chosen “Mission Execution” and “Navigation.” For classes, the descriptions are directly in Python code as shown in Table 1. -

Methods affected by layers

For methods, we select features inside of a class subtree. In this case study, we have chosen “Fly Survey Pattern” and “Emergency Return to Base” within “Mission Execution” subtree. Within “Navigation” subtree, we have chosen “Go to Regular Course” and “Go to Emergency Course.” Those methods are affected by the layers. For methods, the descriptions are directly in Python code as shown in Table 1. While “Clear” layer is activated, “Fly Survey Pattern” and “Go to Regular Course.” are performed. On the other hand, while “Severe” layer is activated, “Go to Regular Course” and “Go to Emergency Course” are performed. Thus, “Clear” and “Severe” are cross-cutting concerns between “Mission Execution” and “Navigation.”

| Requirements | Feature | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Functional | Clear | base layer | Base Layer |

| Non-Functional | Severe | layer | Layer |

| Functional | Mission Execution | class |

class MissonExecution(CPy):

|

| Functional | Navigation | class |

class Navigation(CPy):

|

| Functional | Fly Survey Pattern | method |

@cpybase

def fly_survey_pattern(self):

|

| Functional | Emergency Return to Base | method |

@fly_survey_pattern.layer(Weather.Severe)

def emergency_return_to_base(self):

|

| Functional | Go to Regular Course | method |

@cpybase

def go_to_regular_course(self):

|

| Functional | Go to Emergency Course | method |

@go_to_regular_course.layer(Weather.Severe)

def go_to_emergency_course(self):

|

5.1.2 Feature model code

FeatureIDE can generate feature model code. Figure 5 illustrates a feature model code created with FeatureIDE. The description function in FeatureIDE assists us gather the necessary information for program creation. In Figure 5, “Clear” and “Severe” features are a base layer and a normal layer, respectively. The feature model code represents these features in the rounded boxes on the right.

5.2 Programming and Execution

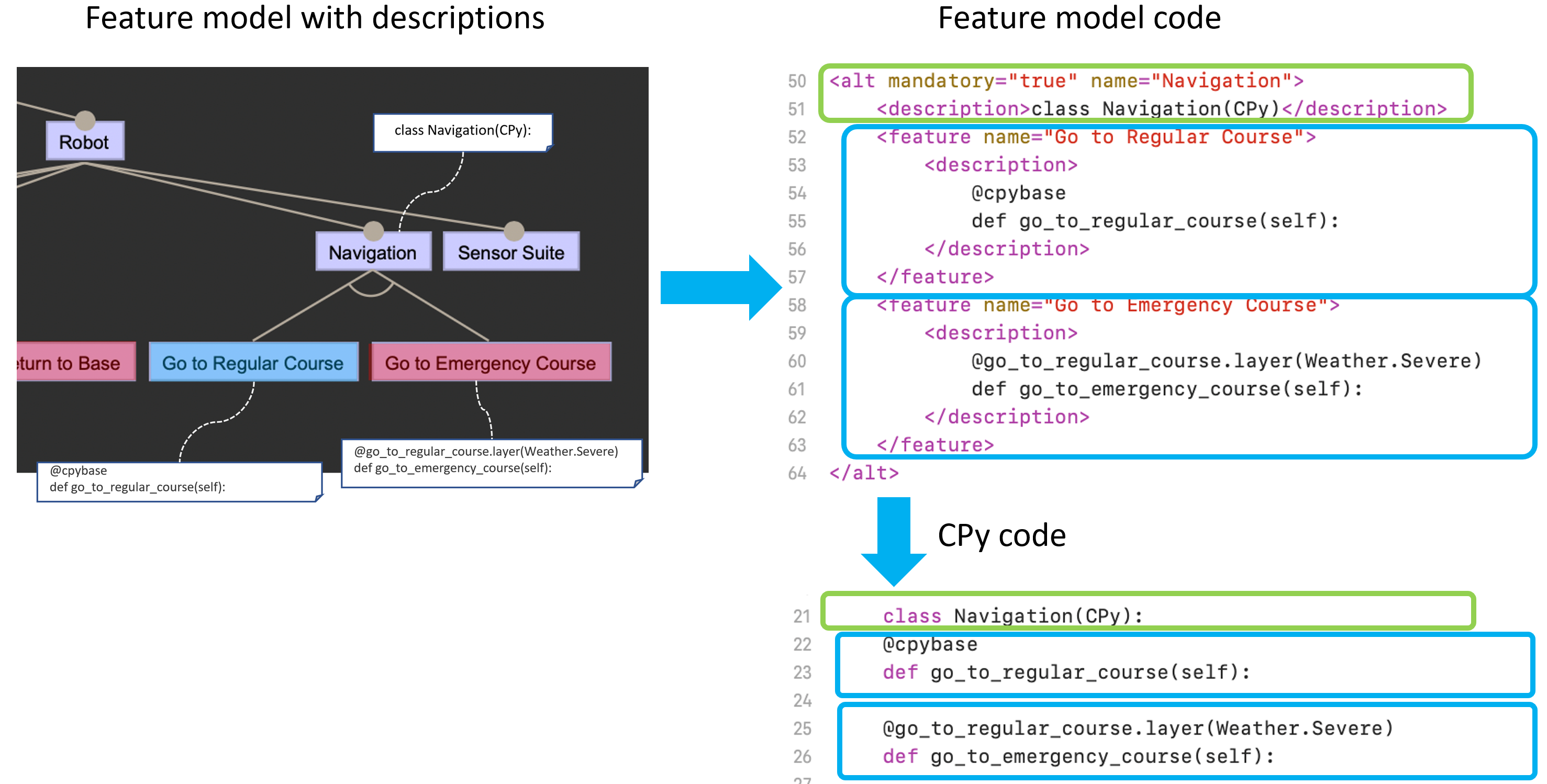

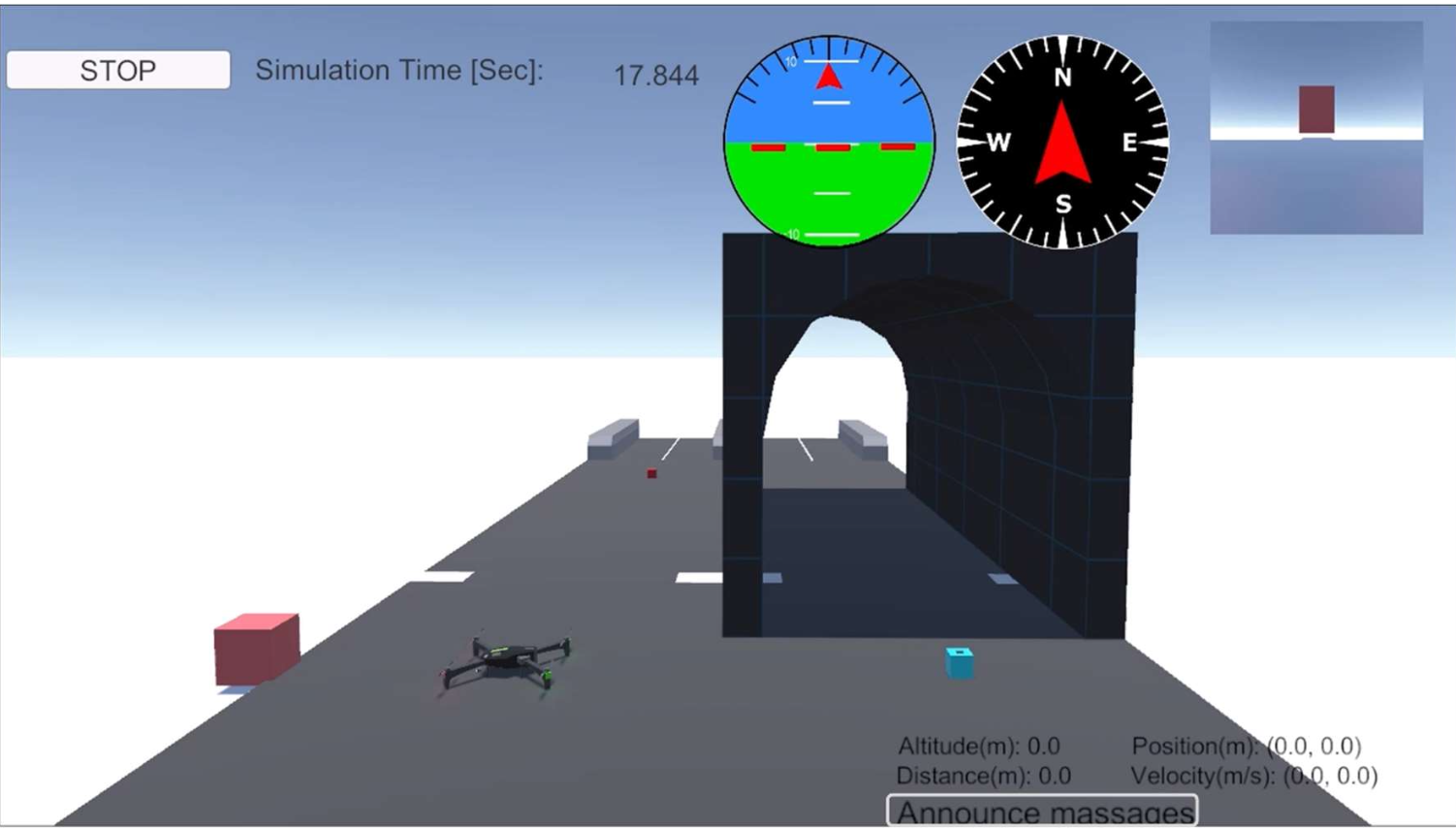

From the feature model code, you can generate blank CPy code containing only layers and classes. Figure 6 illustrates the process of transforming the “Navigation” subtree into blank CPy code. This subtree consists of three features associated with one class and two methods influenced by different layers. The feature model code is divided into three parts: the “Navigation” feature, which includes the class; the “Go to Regular Course” feature, which includes the method affected by the base layer; and the “Go to Emergency Course” feature, which includes the method influenced by the “Severe” layer. These feature codes are concatenated to create the blank CPy code. After that, we will add a program to the blank code and complete it as shown in List 2. Figure 7 shows a snapshot of the drone system execution in Hakoniwa. In this demonstration, the drone flies the tunnel course in the “Severe” weather. In the “Clear” weather, the drone flies left course without the tunnel.

6 Conclusion

This paper focused on two issues (1) clearly defining Non-Functional Requirements (NFRs) and Functional Requirements (FRs), and (2) simulating on a practical IoT platform. To solve these issues, we proposed a robot software development environment called CPy4NFR.

For the first issue, we depicted non-functional requirements (NFRs) in feature models, and the development environment generates layers of CPy, which is a COP language. Through this process, we related an NFR to a COP and dealt with the cross-cutting concern problems by the COP. The main problem with cross-cutting concerns is that NFRs can be missing in each module. We confirmed that the feature model helps us to choose which NFRs are related to the FRs’ modules of classes and methods. However, the relation between NFRs and modules of FRs may not be highly understandable in the current visualization. In our previous study, we proposed COP modeling that can clearly express the relation with layers and classes by extending the package diagram [12]. Future studies will collaborate on CPy4NFR with such modeling.

This paper introduced the main part of the feature model of the drone system. To construct a drone simulator, we needed to develop the surrounding environment. The feature model also assisted us in the construction. Through both feature models, we have felt the need for visualization among multiple feature models.

Regarding the second issue in this paper, the CPy program is executed on Hakoniwa for practical behavior. In this execution, we confirmed that the drone changes behavior based on the weather at runtime. Also, we experienced the same difficulty in flying the drone as with real physical drones and confirmed that Hakoniwa can deal with IoT problems.

Even if we used only Unity or Unreal Engine, we could fly a drone object easily. However, the behavior is different from that of Hakoniwa. Drone objects in Unity or Unreal Engine hold only visualization and position information. To move the object, we only let the object adjust its coordinates. In Hakoniwa, the drone objects contain real information within Hakoniwa-Asset and are affected by surrounding environments. As a result, we need the same operation in Hakoniwa as the real physical drone. In this paper, the application of CPy4NFR was limited to a simple drone system. In Future Work, we will challenge the construction of more realistic robots that integrate several systems that will arise IoT problems.

References

- [1] Featureide. [Online; accessed 2025-04-25]. URL: https://www.featureide.de/.

- [2] Hakoniwa lab llc official page. [Online; accessed 2025-03-21]. URL: https://hakoniwa-lab.net/.

- [3] Robert Hirschfeld, Pascal Costanza, and Oscar Nierstrasz. Context-oriented programming. Journal of Object Technology, 7(3):125–151, march-april 2008. doi:10.5381/jot.2008.7.3.a4.

- [4] Kyo Kang, Sholom Cohen, James Hess, William Novak, and A. Peterson. Feature-oriented domain analysis (FODA) feasibility study. Technical Report CMU/SEI-90-TR-021, Carnegie Mellon University, Software Engineering Institute, November 1990. URL: https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/library/feature-oriented-domain-analysis-foda-feasibility-study/.

- [5] Kyo C. Kang, Sajoong Kim, Jaejoon Lee, Kijoo Kim, Euiseob Shin, and Moonhang Huh. Form: A feature-;oriented reuse method with domain-;specific reference architectures. Annals of Software Engineering, 5(1):143–168, 1998. doi:10.1023/A:1018980625587.

- [6] Pierre Martou, Benoît Duhoux, Kim Mens, and Axel Legay. Beyond combinatorial interaction testing: On the need for transition testing in dynamically adaptive context-aware systems. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW), pages 100–104, 2023. doi:10.1109/ICSTW58534.2023.00030.

- [7] Pierre Martou, Kim Mens, Benoît Duhoux, and Axel Legay. Test scenario generation for feature-based context-oriented software systems. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Systems and Software Product Line Conference - Volume A, SPLC ’23, pages 269–270, New York, NY, USA, 2023. Association for Computing Machinery. doi:10.1145/3579027.3609000.

- [8] Takashi Mori. Cpy. [Online; accessed 2025-04-25]. URL: https://github.com/hisazumi/CPy.

- [9] Yuta Saeki, Ikuta Tanigawa, Kenji Hisazumi, and Akira Fukuda. Contextros: A context-oriented framework for the robot operating system. Proceedings of Asia Pacific Conference on Robot IoT System Development and Platform, 2018:7–12, December 2018. URL: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1050292572129551104.

- [10] Guido Salvaneschi, Carlo Ghezzi, and Matteo Pradella. Context-oriented programming: A software engineering perspective. J. Syst. Softw., 85(8):1801–1817, August 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2012.03.024.

- [11] Hiroaki Takada. Introduction to the TOPPERS project - open source RTOS for embedded systems. In Sixth IEEE International Symposium on Object-Oriented Real-Time Distributed Computing, 2003, pages 44–45, 2003. doi:10.1109/ISORC.2003.1199234.

- [12] Chinatsu Yamamoto, Ikuta Tanigawa, Kenji Hisazumi, Mikiko Sato, Takeshi Ohkawa, Nobuhiko Ogura, and Harumi Watanabe. Layer modeling and its code generation based on context-oriented programming. In Slimane Hammoudi, Luis Ferreira Pires, Edwin Seidewitz, and Richard Soley, editors, MODELSWARD 2021 - Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development, MODELSWARD 2021 - Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development, pages 330–336. SciTePress, 2021. doi:10.5220/0010328303300336.

- [13] Levent Yilmaz. Featuresim: Feature-driven simulation for exploratory analysis with agent-based models. In 2017 IEEE/ACM 21st International Symposium on Distributed Simulation and Real Time Applications (DS-RT), pages 1–8, 2017. doi:10.1109/DISTRA.2017.8167674.